[For more information on individual posters, click or hover over images]

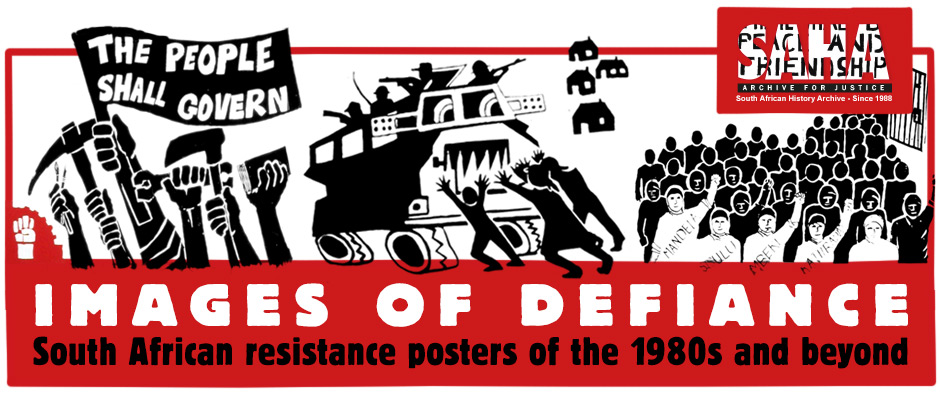

We will continue, despite the hardships

During the 1980s, repression was rife throughout South Africa: in education, with children controlled on their school grounds by security forces; in political life, with political organisations banned and restricted; in the workplace, with labour laws aimed at limiting union activity; in community life, where people protesting against issues such as rent increases were shot down in cold blood; in the media; in cultural life; in the churches and in the courts. Thousands of political activists, unionists, youth and school children risked harassment, long periods of detention without trial, and even death at the hands of the apartheid state.

To prop up the apartheid system the Nationalist government introduced stringent security laws, which increased in harshness and sophistication over the decades. Legislation gave the state wide powers to detain opponents without trial, and to ban people, organisations, gatherings and publications. Under these laws, people could be held in prison for interrogation, as potential witnesses for the state, or as a 'preventative measure'. Access to lawyers and family could be denied and detainees could be kept in solitary confinement indefinitely. Detainees had little if any protection, and many detainees testified to torture and assault. (Security legislation was modified in 1991 to remove many of its most repressive measures.) Over 70 people have died in detention since 1963. (Statistics provided by the Human Rights Commission.)

During the States of Emergency from 1985 to 1990, the state granted itself even further-ranging powers of detention. Over 52 000 people were detained during this time, some of them for three consecutive years. Over 25% of those detained were children, and at times a far higher percentage of detainees were minors.

Ironically, detainees were themselves instrumental in exerting pressure for their release. At the beginning of 1989, one group of long-term detainees after another went on hunger strike, vowing to fast to the death if necessary. With the outside world watching, they gained their freedom one by one, although most were released under severe restrictions.

The releases did not stop the system of detention without trial .But they did lead to the nationwide Defiance Campaign of 1989, in which the Mass Democratic Movement mobilised increasingly effective pressure for change.

Emergency regulations virtually outlawed any form of political activity that might challenge the state. Thirty-two organisations were effectively banned in 1988: boycott actions were prohibited; protest campaigns were forbidden. Police, using teargas, sjamboks, birdshot, rubber bullets and live ammunition continually broke up marches and demonstrations; authorities often proscribed funerals, dictating when and where they could be held and how many mourners could attend. Meetings and conferences were banned, and newspapers closed down for months on end.

The law was used with explicitly repressive intent. Political trials were employed to hamstring democratic leaders, with one central figure after another getting caught up in the snares of treason trials running for months, sometimes years. Bail was usually denied. Many leaders were found not guilty, after years in prison awaiting trial.

Many thousands of people engaging in marches and demonstrations, including children, were arrested and charged with criminal offences. Relatively few cases actually resulted in convictions, but when sentences were imposed they were harsh. The application of the doctrine of common purpose is an example, as in the case of the 'Sharpeville Six'. This group was sentenced to death on the basis that they had formed part of a group which was present at the killing of a community councillor. The sentence was later commuted to life imprisonment after the moratorium on the death penalty in February 1991. By mid-1991 some of this group had been released.

Many thousands of people engaging in marches and demonstrations, including children, were arrested and charged with criminal offences. Relatively few cases actually resulted in convictions, but when sentences were imposed they were harsh. The application of the doctrine of common purpose is an example, as in the case of the 'Sharpeville Six'. This group was sentenced to death on the basis that they had formed part of a group which was present at the killing of a community councillor. The sentence was later commuted to life imprisonment after the moratorium on the death penalty in February 1991. By mid-1991 some of this group had been released.

South Africa also has one of the worst records in the world for capital punishment — 627 prisoners were executed in the five years from 1983 to 1987. But apartheid's legal repressive structures have been increasingly underpinned by more sinister covert forces such as hit-squads, within the country and beyond our borders. Their actions range from irritating harassment to the cold-blooded murder of individuals and groups: their activities include smear pamphlets, bomb threats, slashed vehicle tyres, dead animals on te doorsteps of activists' homes, bricks or teargas canisters thrown into homes or offices, arson, burglaries, kidnapping and assassination. These hit-squads, operating from within the police, the army and local government structures, appear to be badly controlled and ill-informed, but well-armed and well-protected against exposure. They appear to have been responsible for over 50 assassinations of political activists since 1977.

Vigilante groups were also covertly and overtly supported by security forces against communities resisting local authorities. They have been used particularly brutally in the bantustans and in rural Natal, but also in urban communities.

Thousands of people have died in this violence over the last five years of apartheid; recent evidence has implicated the security forces directly in its instigation and in actual attacks.

From 1986 onwards, the state co-ordinated its repressive strategy through the National Security Management System. This structure, presided over by the State Security Council consisting of cabinet ministers and senior military and police officers, formed a countrywide network of Joint Management Centres (JMCs) made up of security police, army personnel and invited members of local government and community. JMCs gathered information on organisations and local activists, attempted to counteract their activities by various means, and co-ordinated local security forces. Evidence also links them to hit-squads and vigilante activities.

Vigilante groups were also covertly and overtly supported by security forces against communities resisting local authorities. They have been used particularly brutally in the bantustans and in rural Natal, but also in urban communities.

Thousands of people have died in this violence over the last five years of apartheid; recent evidence has implicated the security forces directly in its instigation and in actual attacks.

From 1986 onwards, the state co-ordinated its repressive strategy through the National Security Management System. This structure, presided over by the State Security Council consisting of cabinet ministers and senior military and police officers, formed a countrywide network of Joint Management Centres (JMCs) made up of security police, army personnel and invited members of local government and community. JMCs gathered information on organisations and local activists, attempted to counteract their activities by various means, and co-ordinated local security forces. Evidence also links them to hit-squads and vigilante activities.

The cost of the struggle for real democracy in South Africa has been high. Thousands of lives have been ruined, thousands have been killed. Armed with immense legislative and military powers, the authorities have not flinched from crushing opposition. Where the law has not sufficed, they have stepped outside it with monstrous brutality and the arrogance of the unaccountable.

The End Conscription Campaign

At the end of the 1960s, compulsory military conscription for all white males was introduced in South Africa. The apartheid government needed an army ready and prepared to defend its policies against resistance both inside the country and across its borders. Until 1983, opposition to conscription was muted and limited. But late that year, the Black Sash civil liberties group publicly called for an end to compulsory conscription and in response, the End Conscription Campaign (ECC) was formed. Its central demand was for the right of conscripts to choose not to serve in the South African Defence Force (SADF).

The ECC was established as a coalition of many human rights, student, religious and women's groups, all opposed to conscription and militarisation, and committed to working for a just peace in South Africa. The organisation campaigned around the fundamental belief that no person should be forced either to take up arms, or to take life. In South Africa, this stand was specifically linked to the role the SADF played in the townships within the country and in neighbouring states.

The ECC argued that the SADF's primary role should be to serve the interests of a lSouth Africans. Instead, it was being used to defend the system of apartheid against the legitimate aspirations of the majority of South Africa's people, as well as those of the people of Namibia and the rest of Southern Africa.

The ECC identified itself with the cause of the oppressed and sought to contribute to the struggle for liberation. It called for the withdrawal of the SADF from Namibia, Angola and South Africa's townships. for an end to the increasing militarisation of all aspects of South African society, for conscientious objectors to have the right to do alternative national service, and for a just peace in South Africa

Conscription directly affected the white population, giving the ECC a different constituency from most anti-apartheid groups. It therefore had to use new tactics. Conventional political activities like mass meetings, seminars and press conferences were complemented by fun runs, fairs, kite-flying and street theatre. There were cultural events like rock concerts, art exhibitions, film festivals and cabaret. Tens of thousands of colourful stickers, T-shirts, posters and pamphlets were produced. Strong campaigns of support for jailed objectors were mounted.

This dynamic style of campaigning allowed a broad range of people to express their unhappiness with conscription — parents whose sons faced call-ups, school and university students, English-speaking churches, radical Afrikaners, and artists, musicians and actors.

By working among whites against two crucial aspects of the maintenance of apartheid — conscription and the SADF — the ECC won acclaim in the black community, which saw ECC campaigns as contributing to building non-racialism. ECC cooperated closely with mass organisations such as the United Democratic Front and its affiliates, and undertook community upliftment projects in black areas to demonstrate solidarity with township residents.

The government accused the ECC of being a 'communist', 'subversive' organisation contributing to the 'revolutionary onslaught' against South Africa by undermining the army and encouraging conscripts to disobey their call-ups. By the mid-1980s, the ECC was experiencing an endless stream of state harassment. Its meetings and publications were banned, its activists were detained without trial or subjected to intense harassment, and its offices were raided by security police. In 1988, it was restricted.

This repression in no way dampened the ECC's spirit, however. Today it still mounts campaigns against compulsory military service and has done much to assist exiles returning after the unbanning of the ANC and other organisations on 2 February 1990.