[For more information on individual posters, click or hover over images]

We will not ride!

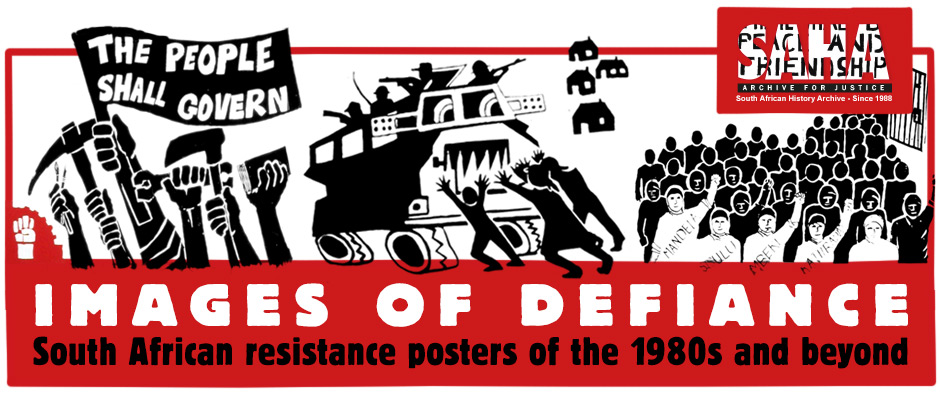

The 1980s will be remembered as the decade during which the pillars of apartheid began to crumble in the face of popular insurrection. Apartheid is not simply a constitutional order that structures political life — it is also a social order that regulates the daily lives of South African people. This regulation is particularly repressive for black people: where they live, how they live, where they work, where their children are educated — all are determined by apartheid laws.

During the 1980s grassroots social movements arose, mobilising and organising communities around three primary issues:

Services, housing and land

Grassroots political democracy

Building new communities

Service, Housing and Land

Beginning with the formation of the Port Elizabeth Black Civic Organisation (PEBCO) and the Soweto Civic Association (SCA) in 1979, 'civics' sprang up in communities across the country. The 1980 schools boycott in the Western Cape provided the impetus for Cape Town's neighbourhood-based civic movement. In Natal, from 1982 onwards, bus boycotts and rent struggles gave rise to civics in both the African and Indian areas.

When the UDF was founded in 1983, civics came together under this national umbrella body, and began to spread even more rapidly, with the Border and Eastern Cape regions becoming the best organised.

The 1985-86 consumer boycotts welded these separate civic organisations into an effective regional movement.

The Cradock Residents' Organisation led the way by emulating the 1950s 'M Plan'-organisation based on street committees, initiated by Nelson Mandela after the Defiance Campaign in 1952. This mode of organisation became a model for the rest of the country in the late 1980s.

Organisations took off quickly in the small Border, and Eastern Cape towns during the 1983-85 period, but it took much longer to filter through the huge urban sprawls and far-flung rural communities in the Transvaal.

The Transvaal regional stayaway in November 1984 paved the way for subsequent united union and community action. But despite the existence of civics in the Northern, Eastern and Southern Transvaal, it was not until the 1986 Transvaal rent boycotts that a Transvaal civic movement emerged with a sense of identity and explicit goals.

In the Bloemfontein area, South Africa's second largest township, Botshabelo, became the focus of a civic movement that linked local issues to resistance against incorporation into the QwaQwa bantustan.

Even smaller rural townships such as Huhudi, near Vryburg, saw community structures develop. Often mobilisation occurred when residents were confronted by a specific problem. In Huhudi, people were threatened with removal from their homes to a location far away within the borders of the Bophuthatswana bantustan.

Grassroots Political Democracy

By grassroots social movements we refer to the classic combination of localorganisations: a civic or residents' organisation concerned with general community matters; a youth congress for the unemployed youth and young workers; a students' congress for school pupils; a women's organisation; an education committee of some kind (a parent-teacher-student association or crisis committee); a trade union local in the larger areas; and a string of local ad hoc issue-oriented committees, ranging from a commuter committee if there is a bus boycott, a consumer boycott committee, a squatters' committee, or an anti-removals committee. In many areas local progressive professional associations —lawyers, doctors, teachers, welfare officers, mental health workers and academics — worked together with the civic structures.

There were no rules as to which organisation should be dominant. Agreed direction was formulated by the leadership of different organisations working together. These were usually a combination of workers, youth, students, organised women and professionals. In certain areas, township-wide co-ordinating structures were established to bring all the organisations together.

The most significant feature of these social movements is that they established deeply rooted structures that brought ordinary people into the decision-making process for the first time. This was done via the street and area committee system. Each street would, at a broad-based house meeting, elect a street committee, which in turn sent representatives to an area (or zone) committee.

The area committees were represented on a township-wide co-ordinating committee. These co-ordinating committees usually began defensively, to protect the community from state repression and sometimes crime. However, in many areas these structures laid the basis for innovative, pro-active development strategies. This network of social movements began to break down apartheid-imposed structures and recreate communities according to democratic principles.

Many community struggles developed in protest against apartheid regulation of basic urban necessities: housing. land, services (such as water and sewerage), transport, health care, child care, and education. This struggle clashed head-on with local government structures, which are notoriously corrupt, elected on extremely low polls (where elections took place at all), administratively inefficient and fiscally un-viable.

Protest would begin on a small scale via petitions, representations and press statements. When authorities ignored these representations, wider collective resources were mobilised in marches, stayaways, boycott action and so forth. Inevitably, such actions were met by harsh security force action, in turn triggering the familiar cycle of protest-repression-violence-counter-violence. The States of Emergency, first declared in 1985 and lasting effectively until mid-1989, were clearly aimed at destroying these grassroots social movements. Meetings and organisations were banned, activists detained and jailed, and army troops patrolled township streets.

As the cycle escalated, grassroots organisation gained a firmer hold, leading eventually — in a few townships — to a situation which was popularly perceived as one of 'dual power' between civic structures and state-run local government. Communities could only take control of their areas for short periods, while under continual attack by the state. However, there were many cases where situations of ‘dual power’ led to negotiations with local-level white business interests and local authorities achieving some redress for black communities.

As well as challenging the state, grassroots social movements also helped to redefine social and cultural relationships within the community. New roles for women in public life emerged; the relationships between generations was continually contested, debated and reformulated: conceptions of citizenship emerged premised on participation rather than helpless passivity; streets and suburbs were renamed after popular symbols and leaders: solidarity against crime became a norm and outsiders seeking to co-opt allies and divide the community were vehemently opposed. In short, communities moved towards forging identities that opposed the logic, values and interests apartheid sought to impose on them.

Since the national detainees' hunger strike in February 1989, popular civic-type organisations have begun to recover from the near-mortal blows many suffered during the Emergency. Throughout the country, the various complex regional movements with their own histories, styles, personalities and issues have begun to re-emerge. This is testimony to the durability of civil society, which, if it continues to develop as it has to date, should provide a sound and robust foundation for a future democratic and just South Africa.d, out of this frequently violent confrontation between local governments and the communities emerged a commitment to local democracy that will help shape a future constitutional order.

Link to SAHA Women Hold up Half the Sky Virtual Exhibition

Link to SAHA Youth Virtual Exhibition

Link to SAHA Workers Commemoration Virtual Exhibition