It was mining — mainly of gold — that catapulted South Africa into the industrial age. But the gold-bearing 'reef of the Witwatersrand was of very poor quality, so high profits depended on low production costs. The cheapest way for the mine-owners to get the gold required vast numbers of unskilled workers using labour-intensive methods. Britain obliged by sending its armies to destroy the independent African societies, invade the Boer republics, and create a Union of South Africa largely beholden to the powerful Chamber of Mines. The supply of African labour was assured by imposing taxes on peasants, restricting their access to land and markets, instituting pass laws and housing workers in compounds.i

White workers, in contrast, had far more clout: most skilled labour on the mines was performed by immigrants with a militant tradition of West European craft unionism, which won them a relatively high standard of living and protection from undercutting by cheaper black labour. Early on, white workers formed a kind of alliance with capital — both profits and higher wages deriving from the extreme exploitation of black workers.

But relations were not always harmonious. Attempts by the mining houses to cut costs and increase profits by replacing white workers with blacks whom they paid much less led to bitter strikes that climaxed in 1922. A miners' strike which the state helped the Chamber of Mines to smash saw white workers attack scabbing black workers and is remembered for the slogan, 'Workers of the World, Fight and Unite for a White South Africa!' Once it had put down the 'Rand Revolt' the state acceded to the white workers' racist demands, thus buying fifty years of relative peace on the white labour front.ii

Black workers also organized on the mines: widespread job actions for better wages and conditions culminated in the 1920 miners' strike, involving 70,000 workers over a period of twelve days. Most of the strikes were spontaneous and workers lacked the leverage to sustain their actions. Still, it was the fear of this growing black worker militancy that had prompted the government to put long-term security before short-term profits and concede the demands of the Rand Revolt.

The fear that obsessed me above all things was that owing to the wanton provocation of the revolutionaries, there might be a wild, uncontrollable outbreak among the natives.

Prime Minister JAN SMUTS, 21 March 1922, addressing parliament after the white miners' strike was brutally crushed with the aid of bomber aircraft and tanks, resulting in some 250 deaths, 1,000 arrests, and the execution of four strike leaders

Not all white workers embraced the racial division of labour. A section of white labour broke with the mainstream and demanded a unity of the working class that transcended racial barriers. Some of these whites were West European artisans attracted by the mining boom, others were less skilled refugees from anti-Jewish repression in Eastern Europe, and a few were British Army veterans who had stayed on in South Africaiii after the Boer War. In 1915 they broke from the racist South African Labour Party and formed the International Socialist League (ISL), the first political group to attempt to organize non-racially and build a mass base among the oppressed.

White Workers! Do you hear the new Army of Labour coming? The native workers are beginning to wake up. They are finding out that they are slaves to the big capitalists. But they want to rise. Why not? They want better housing and better clothes, better education and a higher standard of life.

White Workers! On which side are you? Your interests and theirs are the same as against the Boss. Back them up! The Chamber of Mines will be asking you to take up the rifle to dragoon the Native strikers. Don't do it!

ISL LEAFLET issued during the black miners' strike of 1920

The ISL had already begun working with the newly established South African Native National Congress (SANNC, later renamed the African National Congress). The attempts of the white radicals at organizing black workers led to the founding of South Africa's first black trade union in 1917, the Industrial Workers of Africa (IWA). In 1919 the new Industrial and Commercial Workers Union (ICU) led a strike on the Cape Town docks that involved both African and coloured workersiv Those arrested that same year after a strike wave on the Rand included blacks and whites, and the 'public violence' trial that followed was the first in South African history in which blacks and whites were charged together for political offences.

This glimmer of non-racialism in the early twentieth century was overshadowed by the firmly established, if not always stable, political alliance between white labour and capital. The promotion of whites as supervisors of less skilled black labour facilitated the emergence of a 'labour aristocracy' in league with industry and government against the blacks below them. Members of the ISL who formed the Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA) in 1921 began to realize that the country's problems could not be understood solely as conflict between social classes: evidently, relations between the races were also vitally important.

"I remember in 1930 or '31, during the Depression, seeing a mixed white and black procession demonstrating for jobs and wages and bread, and this impressed me greatly. You might say I had a romantic idea, but then I think people with a radical outlook who reject the existing social system are romantics — some people call them mad. You have to have a great deal of confidence and faith, you have to look for little things like that as beginnings. Now I was shaping the ideological framework at that time, and this gave me evidence of a non-racial class approach. But that had to mature, though it was difficult to mature it in the South African situation at that time. You see, the Communist Party of South Africa had a theoretical platform, which is important. As far back as 1928, Sidney Bunting and Eddie Rouxv the two leaders, had gone to Moscow and they'd been ticked off by the Communist International. At that time there was a group of American negroes who were very vocal in the Comintern, and they were represented by a couple of very voluble fellows who criticized the communists of South Africa very savagely for being a white supremacist party,vi and insisted that the correct policy for the communists to adopt was to launch a programme in support of the national democratic revolution, in terms of resolutions adopted by the Communist International as far back as 1920 and '21.

There's a whole history of this, communism and the national liberation movement — this was before my time. Basically the communists had been oriented towards white workers, thinking the white workers would be revolutionary. Now by 1928 that optimism had ebbed, died away, and I think the visit to Moscow had opened their eyes that their true function was to work with the African working class, and they thereupon proceeded to do it.

It wasn't easy to make this shift. The white communists who had led the party since its inception and even before that had to turn right round and reject their former colleagues and make an approach to blacks, whom they had no real contact with or experience of. You see, the communists had launched this — we were pioneers in that respect. Nobody else had ever come forward with this notion of a black republic and a black majority."

JACK SIMONS, Communist Party member active from the 1930s

The South African communists returned home from Moscow having pledged to implement the Comintern's call for 'an independent native South African republic as a stage towards a workers' and peasants' republic, with full, equal rights for all races'. The 'Black Republic' thesis caused strife within party ranks for the next decade, but it also generated a transformation of both the membership and then the leadership, from mainly white to overwhelmingly black.

Dear Comrades,

Our party has and is suffering owing to being too Europeanized. The European language is not blindly applicable for South Africa. In Europe class consciousness has developed immensely whilst here national oppression, discrimination and exploitation confuses the class war, and the majority of the African working population are more national-conscious than class conscious.

My first suggestion is that the party become more Africanized, that the CPSA must pay special attention to South Africa, study the conditions in this country, and concretize the demands of the toiling masses from first-hand information, that we must speak the language of the Native masses, and must know their demands. That while it must not lose its international allegiance, the party must be Bolshevized, become South African not only theoretically, but in reality. It should be a party working in the interests and for the toiling people in South Africa, and not a party of a group of Europeans who are merely interested in European affairs.

With revolutionary greetings,

Yours fraternally,

Moses M. Kotane

Letter from MOSES KOTANE, CPSA member who became general-secretary in 1939 and served until his death in 1978, writing from Cradock to the Johannesburg District Committee, 1934

While increasing numbers of blacks endorsed the non-racialism of the CPSA, others joined the growing non-racial trade union movement, along with whites who had embraced the goal of a 'Black Republic'.

"I came to South Africa on 6 November 1929, when I was 15 years old, going on for 16, and the very next few days I was introduced to people who were supporters of the Communist Party. I went to do shopping for my sister, so when I was buying the vegetables I saw workers coming out from the factory. I asked them whether they have a union and if they are members of the union. One of them said they have a union but they are not members of the union, and the others said they have no union. And I walked off with the idea that here in South Africa is virgin soil!

The fact that these workers were black didn't bother you?

Being Jewish, I knew of the oppression that the Jewish people had in the ghettos, and also the fact that they were discriminated against in Tsarist Russia from entering universities and from learning professions, trades. There was a kind of apartheid. Therefore race discrimination and job reservation in South Africa was very close to me because it is part of my upbringing. I got to know about the white 'civilized labour policy', so that all fitted in with the anti-semitism that was present in Tsarist Russia and in Poland and even in Latvia, particularly in the ghettos. I never felt — honestly, on my word of honour — I never felt odd working among African or coloured people, working with them together. We were one. I never felt when I was with Comrade Moses Kotane that he's African and I'm white, and he never felt that I'm white. He used to say to me, 'With you I feel one.'

I remember the first holiday I had in Cape Town, my mother took me to introduce me to her relatives, and my cousin saying to me that I'll never be able to marry, you know. I was still going on for 17 years and he's telling me there won't be a Jewish boy: it's already known that I walk about with coloureds and blacks and no Jewish boy will marry me. I just looked at him — to me this was completely nonsense that he was speaking to me. I wasn't going to alter my lifestyle.

On 16 December 1929 a demonstration was going through Adderley Street, coming up from Plein Street, led by Eddie Roux and others, Africans.

I quickly go to the manager's desk and I say, 'May I take an hour off — my lunch hour — or I'll work it off later on?' and she said yes, and I just quickly went and joined the demonstration. So there were only two whites, Eddie and myself. However, when I came back from the demonstration an hour later — I looked at my watch so that I shouldn't be late — I was called into the office and told that I can't work there any more because I participated in this demonstration. So I lost my job.

When you first met black people in South Africa, did you discuss this issue of colour?

No, I didn't. I completely felt at ease with them, with Johnny Gomes, with [E. J.] Brown, with James La Gumaix So I got involved with those people and I was introduced to the discussion on the 'Native Republic', the Black Republic. Now that is something of great honour to the Communist Party of South Africa, because it was the first and only organization that put forward majority rule — the first organization on the African continent that had put forward the idea of one vote for every person, irrespective of race and colour. And there was raging the debate about it — whites in the Communist Party who hadn't approved of it left the party.

Well, I was completely in agreement with this slogan of Black Republic, because that was to me a sensible thing, democracy. I couldn't visualize anything else. One of the comrades had said that I should give them the reasons why I am supporting the Black Republic, so I put down the reason as democratic rights: Africa is black, South Africa is a black man's country, and therefore it should be a black republic. I said to them, 'But this is ordinary democracy, one man, one vote — we can't tolerate this white autocracy here.' So they accepted me like this.

What about the rank-and-file union membership, did they accept you? And the white workers, how did they feel?

In all the Cape Town factories you had a mixed group of workers, whites and coloured, working together. There wasn't this nonsense that came afterwards. Now the first time that I succeeded to organize a union was the Commercial Employees Union. I worked in the shop and I organized the shop assistants. You know that we used to work Christmas — before Christmas Day and before New Year's Day and before Easter Day, till eleven o'clock at night, Fridays till nine p.m. — and we succeeded in reducing the working hours.

Now at this stage, when I got so many benefits for them, I walked in the street with Comrade Shuba and two of the shop stewards, two Afrikaans girls, they went and lodged a complaint with the Cape Federation of Labour Unions that I was walking with a kaffir and insulted them by greeting them. So they organized a big campaign that I must be removed as the secretary of the Commercial Employees Union — that was all done by the reactionary leaders of the Cape Federation of Labour Unions. So I'm summoned to a meeting and they expect that I would resign. But I didn't resign. I made my speech and I said that I'll help any worker, irrespective of their colour or race or religion, to improve their wages and conditions of work. I said, 'What you have, the benefits you have obtained as a result of my work, is due to the fact that Comrade Shuba had trained me.' And elections took place, and although one of the trade union federation leaders went round and told people not to vote for me, I got re-elected with flying colours. And then this matter is discussed by our comrades and it's all agreed that I'm in a way wasting my time on these white girls — that I should devote all my energies in organizing the coloured and African workers.

Why was that decided?

Because the base for our work is the black people — that is as it was and as it is still today, you see."

RAY ALEXANDER, who came to South Africa as a young refugee from Latvia and helped organize non-racial trade unions from the 1930s to the 1950s:

As it happened, that lesson learned — that the impetus for changing South Africa would come from the most exploited group — was not so straightforward. Some trade unionists felt that while they endorsed non-racialism in theory, in practice a form of racial differentiation within the unions offered tactical advantages in building a powerful workers' movement.

For others, this represented a betrayal of principles and undermined the position of black workers.

"In fact, the early beginnings of the clothing industry in the Transvaal came mainly from the Afrikaner community, so that my first job was working for a firm which had a Jewish employer and mainly Afrikaner girls. There was always a strict line barring you from any close relationship with the whites.

You worked in the factory and you saw to their needs as far as work was concerned — out in the street you were nobody.

Were these Afrikaner women members of the union?

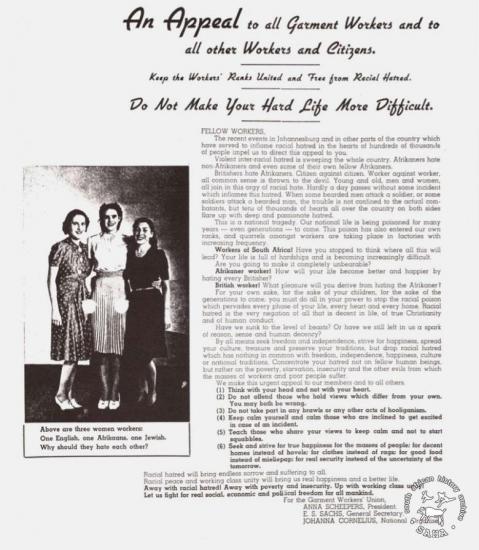

Yes, well, it's a peculiar thing about the way things go in South Africa. Solly Sachs had established the Garment Workers Union, and initially it was based on membership who came from the Afrikaner community, you see, mostly women. At some stage, when I suppose they could not get enough white labour for the industry, there was then an influx of coloureds and Indians, you see. Their numbers were growing and so around 1939, '40 they felt that they'd have to do something about providing some sort of union membership for these coloureds and Indians, and so they called a meeting and established the Number Two Branch.

Now Solly's attitude was that because the Afrikaners were essentially very racist in their outlook, you couldn't get them to sit at the same table with blacks to discuss their problems which were mutual to themselves, and so the Number One Branch would meet and discuss the same problems as the Number Two Branch — but separately, you see. We then reached a stage where we felt that since they professed that trade unions looked after the interests of all workers, irrespective of race, why did Solly and his colleagues call themselves socialist or whatever, when in fact, they are carrying out a policy which means that we are apart? So that we found ourselves in the Number Two Branch actually waging a campaign to bring the union together. But they wouldn't have it, because the feeling expressed by Solly Sachs was that if we did so the Afrikaners would resent it and it would split the union.

It's a strange thing, there were lots of contradictions. There was a dispute in 1943 when we were all locked out by the employers — some 400 factories throughout Johannesburg were just closed. I'd been working for this firm for a number of years, and though working with these Afrikaner girls meant that we kept our distance from each other, in the factory there was a kind of link. I was busy running in between the factory and the union office and so forth, and they wanted to select a shop steward. They found that the one they had was useless, and an Afrikaner girl said, 'Well, there's Phillips, let's make him our shop steward.' And so a message was sent across to our union office: 'They say they want Phillips to act for those girls in South African Shirt and Underwear Manufacturers.' And the union officials, Solly Sachs and his colleagues, turned it down. They said, 'No, you must appoint a white person.'

Another time it was decided that there should be a cutters' association, and most of the cutters in the industry then were Afrikaners, with a sprinkling of coloureds and Indians. And this meeting was called and we discussed the question of forming this association, and it was all agreed and they said we need a chairman. So an Afrikaner got up and he says, 'I nominate that man.' And they said, 'Who?' And he said, 'Phillips.' So I was appointed unanimously at this meeting.

Solly was away and returned a few days later and saw the minutes of the meeting, called me to the office and he said, 'You shouldn't have become the chairman, you should have let an Afrikaner become the chairman.' I said, 'But they elected me and it was unanimous.' Well, he wouldn't have it.

But this is something on which I was in dispute with Solly over a long, long period. I thought, here was an opportunity where we might be able to break those barriers by these little links.

This was the thing about the Garment Workers Union: it never politicized the workers. They made them just think in terms of bread and butter — unlike us, who felt that we didn't fight for bread and butter issues, but wider issues, that politics comes into it. I think when I was elected as chairman, and where these workers wanted me to be their shop steward, an attempt should have been made to try it out and not to just reject it outright, and to see what would happen. But Solly adopted a very special position: he felt that the time would come when the Afrikaners would open their minds, you know, and that they would actually lead to change things in South Africa.

And what did you feel, having worked with these whites on the shop floor?

I felt that in order to advance ourselves as workers we would have to group ourselves together, and by the force of our numbers and our strength and our politics and our links with the movement in general, this is how we would come to be respected. But then it had gone too far, and this is why the position is what it is today, that the minds of the whites have been so completely warped."xii

JAMES PHILLIPS, a cutter in the garment industry and chairman of the Garment Workers Union Number Two Branch for 'non-Europeans' from 1940 until his banning in 1953

NOTES

i One hundred years later, the National Union of Mineworkers responded to 'the pomp and advertising hype of the Chamber's centenary celebrations' with a full-page advertisement in several South African newspapers labelling the Chamber 'the exploiter of our nation', citing a pay differential between whites and blacks of ten to one, and charging that 'racial segregation and the denial of basic human and trade union rights are the cornerstones of the industry'.

ii Apart from the Garment Workers Union in the 1930s and 1940s, there was little serious disruptive action on the part of white labour until the 1970s.

iii The first category included ISL and CPSA founder member Bill Andrews, the only South African ever elected to the executive of the Comintern; the second included Solly Sachs, a Lithuanian immigrant who led the Garment Workers Union for more than twenty years; the third, S.P. Bunting, an early CPSA chairman who advocated the recruitment of Africans. For a more detailed analysis of early white radicalism in South Africa, see John Daniel, 'Radical Resistance to Minority Rule in South Africa: 1906-1975', unpublished Ph.D thesis, State University of New York at Buffalo, 1975.

iv The white railway union participated in separate but supportive action with the ICU and IWA until the government responded with a concession that prompted the white workers to scab.

v The gravity of this concern is evidenced by extensive government probes into the 'poor white problem' in the first three decades of the twentieth century.

vi One of the first South African-born white communists.

vii The Negro Commission, a sub-committee of the Colonial Commission of the Sixth Congress of the Comintern, which analyzed race and nationalism in South Africa and the US.

viii Sheltered employment for unskilled whites, extended by Prime Minister Barry Hertzog's Pact government (Nationalist-Labour) in 1924.

ix Gomes, Brown and La Guma (father of ANC leader and author Alex La Guma) were CPSA members from Cape Town's coloured community

x James Shuba was secretary of the Cape Laundry Workers Union, elected to the first national council of the South African Trades and Labour Council and a member of the CPSA.

xi A derisive South African term for blacks, stemming from an Arabic word meaning 'infidel'.

xii For more on the vision of non-racialism peculiar to Solly Sachs's trade union Experience, see Leslie Witz, 'A Case of Schizophrenia: The Rise and Fall of the Independent Labour Party', in Belinda Bozzoli, ed., Class, Community and Conflict, Ravan, 1987