South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) had complex engagements with questions of gender, and the experiences of women – both during the liberation struggle, and at the TRC itself. The fact the women and men experienced apartheid differently, and faced different challenges in interacting with the TRC, was a key issue that required the TRC’s attention.

However, critiques of how the TRC handled women-specific issues abound. In terms of the TRC’s policies and frameworks, it was clear that gender-specific considerations had not been taken into account. The TRC”s “gender-blind” approach to dealing with the past implied that no distinction would be made between men and women’s experiences, despite the fact the women and men experienced apartheid differently, and thus faced different challenges in interacting with the TRC.

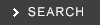

Black and white photograph of delegates at the launch of the Transvaal South African Domestic Workers Union Living Wage Campaign, taken by Anna Zieminski for Afrapix on September 3, 1988.

Archived in SAHA collection as AL2547_11.9.10.

Read the transcripts for the TRC's Special Hearing on Women here

For example, Khulumani Support Group highlighted the fact that rape and sexual violence was subsumed under the category of “serious ill-treatment”, and not considered a category itself by the TRC. Compounded with this, was the fact that rape was not explicitly defined as a political act by the TRC’s definitions, and was therefore excluded from crimes for which amnesty could be sought. Perpetrators intending to come forward to testify would be liable for prosecution, resulting in very few admissions of rape from perpetrators. Also of concern, was the issue that the TRC’s public platform, alongside cultural and personal obstacles, made the reportage of rape and sexual violence committed against women during apartheid, difficult for some to talk about.

Another difficult gender issue facing the TRC, was the fact that many women came to testify about the men in their lives – husbands, sons, relatives – who had been the direct victims of murder, torture or disappearance. The role of reportage fell to women, and arguably gave the impression that women were mere passive bystanders to the horrors of the past. An attempt by the TRC to remedy this, was the creation of a Special Hearing for women, where individuals were invited to testify.

Take a look at SAHA's Women's Day gallery here

This was a way for women to tell their own stories of suffering – stories such as Nozibonelo Maria Mxathule’s clash with police in March 1986. A member of the ANC Youth League, Mxathule was on her way back from a funeral for comrades who had been killed by the police, when she was part of a group of young people forcibly detained by police officers. Taken to an undisclosed location, she and her fellow detainees were then tortured by the police:

“They ordered us to strip naked. They were in a line, a row. They told us to face the wall. We stripped naked, all of us, against the wall, boys and girls the same. They assaulted us...They threw us out on the grass and poured water on us and left us there. At about six o' clock to seven in the morning they woke us up and ordered us to leave. We could not, it was difficult. Some of us were taken by caspirs and some had already passed away. We were lying on the lawn. Some of us were taken to the mortuaries.”

The catharsis of statement-making, however, was not the only reason women came forward to the TRC. Those who had been left as the sole breadwinners for their families had very practical concerns about how the TRC was going to help them not only testify at the TRC – but assist them afterwards. They remained skeptical about the TRC process. In her TRC Oral History Project interview, Ruth Lewin explains:

“I remember when our logistics officers went out [to the Northern Cape] and there were a couple of mothers who said, what are we going to get out of this? They were very, very cynical about giving their testimony and making statements. And at the end of it all they agreed and said that all that they really want is for their children…because their husbands were killed…to have an education”.

November 2014 saw the South African government promulgate regulations that would provide education assistance to victims of apartheid - eleven years after the TRC handed over its final report in 2003. Deemed insufficient and exclusive, limiting access to assistance to those with a TRC victim registration number, these regulations have a long way to go before they could fulfill the hopes of those women interviewed in the Northern Cape – and all other victims of apartheid.

Women Hold Up Half the Sky - SAHA's virtual exhibition documenting women's contribtutions in the struggle against unjust laws and gender-based discrimination.

Women formed an integral part of the struggle against apartheid - as combatants, advocates, witnesses and organisers. They experienced particular kinds of pain, humiliation and abuse in detention, and continue to carry the weight of responsibility as their partners, relatives and children were murdered and disappeared. This August, we honour and respect the role women played in both securing South Africa’s freedom, and testifying to her brutal past.

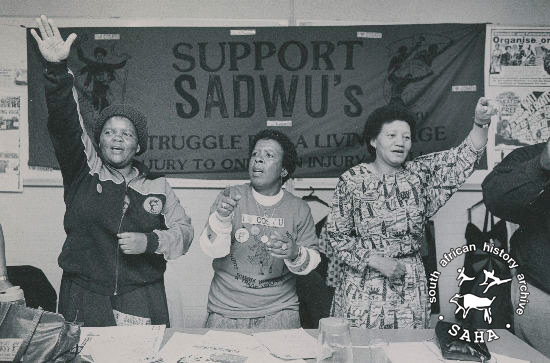

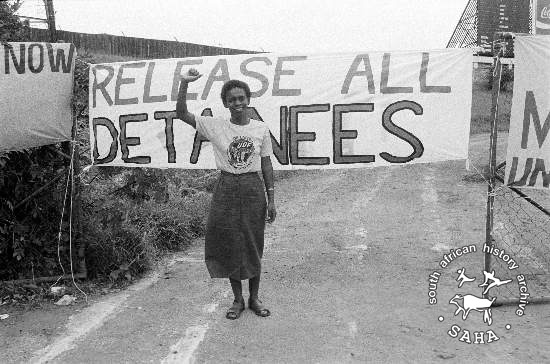

Black and white photograph of Debra Marakalala from Tembisa, taken by Gille de Vlieg at the Freen Mandela Rally held in Durban, December 15, 1985.

Archived in SAHA collection as AL3274_C43.1.