[For more information on individual posters, click or hover over images]

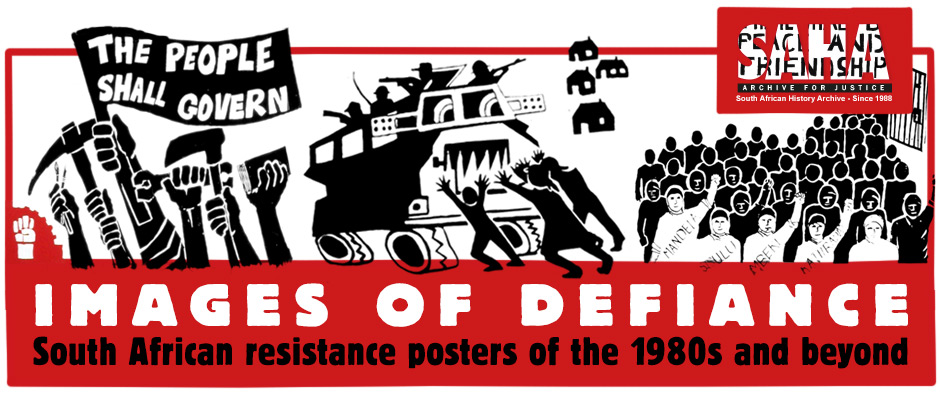

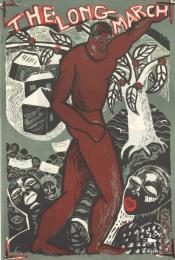

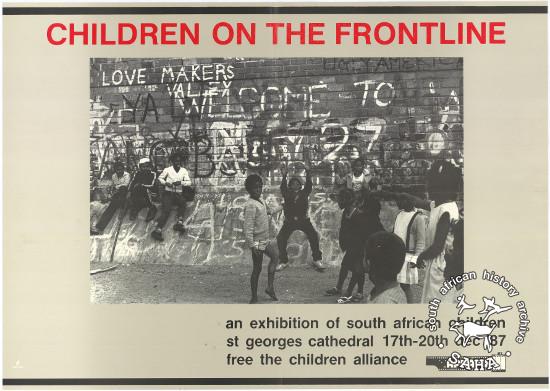

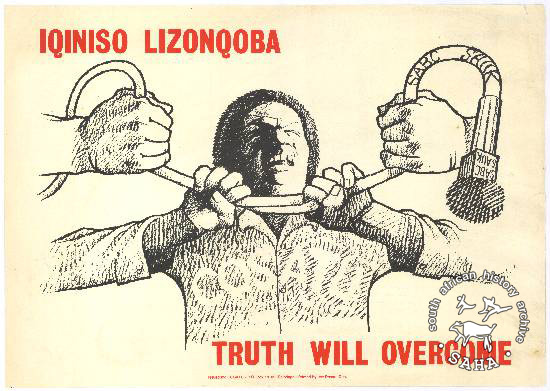

The grassroots political mobilisation of the 1980s sparked off a massive surge in 'people's culture'. As people found the political voice to shout out their angers, beliefs, griefs and victories, they learned to express these also in cultural forms — from toyi-toyi to jazz, from poster-making to workers' theatre and oral poetry. Youth, women, workers, students and conscientious objectors began to create the image of a people with dignity, of a community striving for the values of non-racialism, democracy and an end to economic oppression.

Apartheid culture vs people's culture

Apartheid society has, over the decades, severely distorted the practise and perception of culture. 'Culture' was used to justify colonialism, with claims that European civilisation was better, that African societies were 'barbarous' and 'savage'. In South Africa, this remained a basic presumption. Apartheid law also divided the black population into 'ethnic groups', supposedly based on pre-colonial kingdoms and cultures of the region. Apartheid apologists had a stake in identifying and maintaining such 'traditional' groups. Just as apartheid theory denied the existence of permanent black residents in urban areas, apartheid culture refused to admit the existence of an emergent black urban culture.

The principles of apartheid culture infused the education system (both bantu education and Christian National Education), the mass media (radio. TV, and newspapers), and all state-linked structures involved in funding the arts.Of course, people developed their own forms of cultural expression despite official attitudes and structures, and the lack of resources. With the earliest shanty-towns and illegal shebeens came marabi and the roots of South African jazz, a tradition which produced a number of internationally known musicians.

The principles of apartheid culture infused the education system (both bantu education and Christian National Education), the mass media (radio. TV, and newspapers), and all state-linked structures involved in funding the arts.Of course, people developed their own forms of cultural expression despite official attitudes and structures, and the lack of resources. With the earliest shanty-towns and illegal shebeens came marabi and the roots of South African jazz, a tradition which produced a number of internationally known musicians.

In the 1950s, writers centred around Drum magazine developed a distinctive style of prose writing. The early 1970s saw a wealth of poetry and theatre linked to the student and black consciousness movements. Directly tied to political defiance, songs such as Meadowlands (protesting the 1950s Sophiatown removals) and the poetry and songs of Vuyisile Mini (a trade union and ANC leader executed for sabotage in 1964) became part of the 'folk culture' of the townships.

Culture as a 'weapon of struggle'

In the 1980s cultural activists began to develop what was termed 'people's culture' as a tool for mass mobilisation against apartheid. The concept was first publicly adopted in 1982 in Gaborone, at a conference entitled 'Culture and Resistance'. Taking a stand against the notion of the elite artist working in isolation, the conference called on cultural workers to commit themselves to the oppressed communities, and to explore the expressions, realities and demands of grassroots South African society.

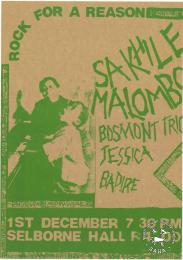

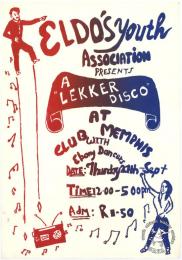

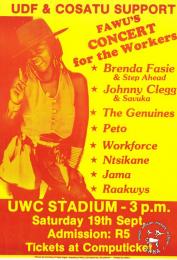

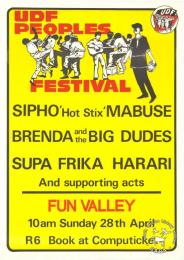

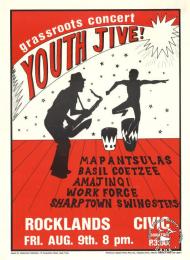

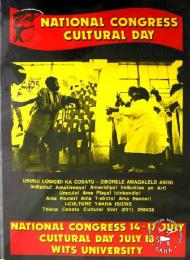

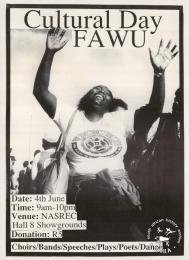

The birth of the UDF in 1983 provided a platform — often literally — for this vibrant cultural voice. The resurgence of mass organisation brought a new mood of empowerment, creating an environment alive to the importance and potentials of cultural work. Hundreds of community events opened up the space for untold numbers to share in some of the creativity, imagination, humour and defiance so alive beneath the squalor, pain and violence of the townships.

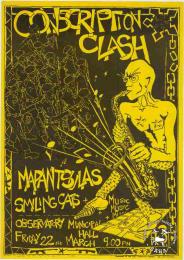

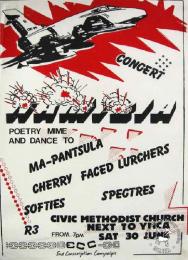

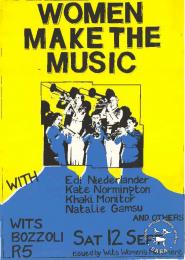

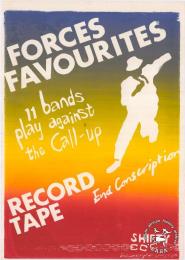

Struggles within various sectors of the democratic movement were taken up in cultural campaigns. The End Conscription Campaign deliberately worked to build an anti-military culture, encouraging anti-war murals, rock groups, and theatre. Similar strategies were used to highlight the women's struggle.

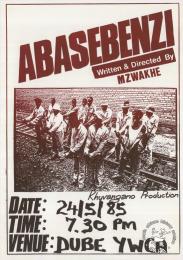

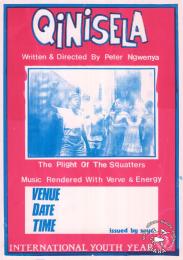

The founding of the Durban Cultural Workers Local in 1984 sounded the first note of the national worker cultural movement. Located within the black trade unions, and often inspired by ongoing strikes and issues, this movement has produced hundreds of plays, a burst of oral poetry, dance, and film.

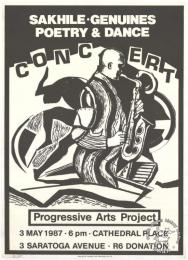

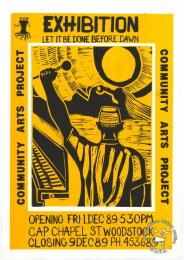

As people began to explore cultural forms to express their understandings and demands, a number of communities introduced art training programmes, such as the Community Arts Project in Cape Town, Funda Centre in Soweto and the Alexandra Art Centre outside Johannesburg. These centres played an important role in spreading art skills and ideas, and served as locations for cultural productions.

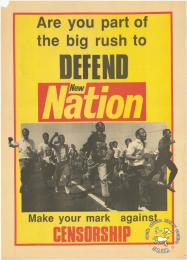

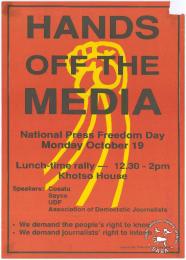

The power of cultural activity of the mass movement helped to weaken the state's stranglehold on broadcasting, record companies, and other cultural resources.

Establishment cultural institutions gradually and grudgingly began to use the language of popular culture. Thus, even the more formal spaces of culture saw a burgeoning of popular theatre, music, art and video. Museums, art festivals and literary competitions, once bastions of conservatism, have begun to look for broader participation in a bid to avoid being by-passed by history.

International outrage against apartheid led to the cultural boycott. This had a two-fold effect: it provided more space for South African artists to develop their own styles and forms; and it acted as a focus for people within South Africa, making them more conscious of the negative influences of international culture that appeared here.

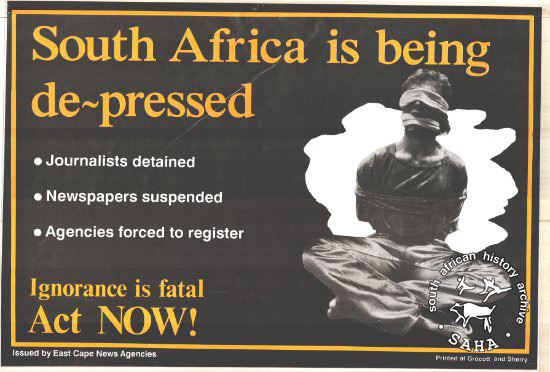

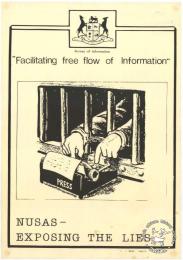

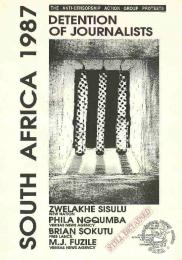

Repression

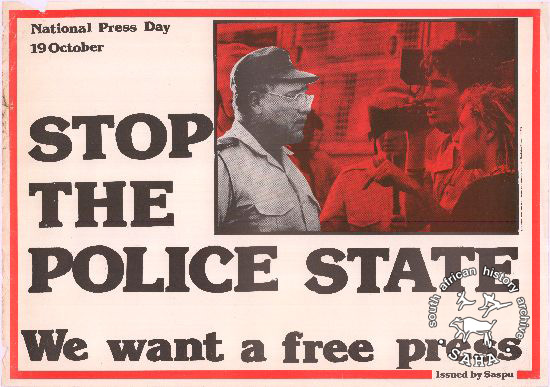

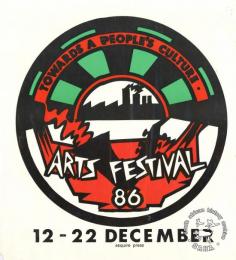

When the state cracked down on the mass movement in 1985, cultural activities assumed a new role. With political rallies, meetings, and banning of organisations, cultural occasions provided a forum for people to come together to witness their strength and celebrate their commitment. The state recognised the significance of this by banning many explicitly cultural events — the most prominent being the 1986 Cape Arts Festival. Its slogan would have been 'Towards a People's Culture'.

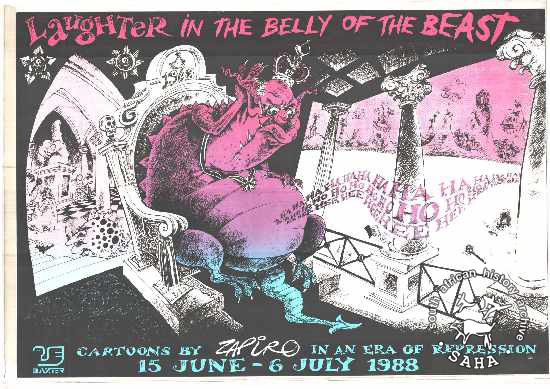

Cultural activists, like so many community workers, also suffered directly under the State of Emergency. Police raided community art programmes, and detained students and teachers. Books were banned and toyi-toyi was declared a revolutionary activity. Many cultural workers went into hiding.

By 1987 the pressures on the mass movement had left many structures barely functional. The UDF Cultural Desk was launched to facilitate the growth and organisation of local culture. It also sought to assist in clarifying and implementing the international cultural boycott.

The Desk's first job was to co-ordinate the conference entitled 'Culture in Another South Africa' (CASA). CASA brought exiled and internal progressive workers together in Amsterdam, Holland, to talk, to debate the direction of progressive culture.

The conference endorsed earlier positions on theneed to build cultural organisations. It also changed the thrust of the cultural boycott, calling for cultural exchange between the international community and the oppressed people of South Africa, while maintaining a ban on those who were not prepared to take a stand against the apartheid system.

The event served as an important rallying point, and a showcase for the range of exciting progressive cultural work being done in South Africa. But cultural workers returning from CASA came back to repression and the on-going State of Emergency: many of the resolutions taken there are yet to be fulfilled.

Culture in a future South Africa

South African society finds itself poised on the edge of vast and uncertain changes. Cultural workers aligned to the democratic movement have been forced to look again at the place of culture within their communities, and to evaluate their work in terms of what they can contribute to a future society.

Albie Sachs, in a paper to an ANC cultural forum in 1989, challenged cultural workers to produce more works 'which by-pass, overwhelm and ignore apartheid'. He echoed the sentiments of other cultural workers, that slogans and overt political content by themselves cannot replace the subtlety, complexity and ambiguity that effective cultural work demands.

What is the role of culture in the period of transition? How can our work help 'open wide the doors of culture?' How can we correct a situation where for so long the state has pumped resources into facilities and opportunities for the minority alone? And what kind of cultural work is needed to end the ethos of oppression, to go beyond angry reaction to apartheid? How do we start building that boldness, creativity and self-confidence needed to transform South African society?

The discussion and debate on the role of culture in building our new society is likely to continue long into the future.

One thing is certain: progressive cultural workers will be as important in the unfolding of a new South Africa as they have been in breaking down the oppressive and racist consciousness of the old South Africa. They will be creating images —through plays, poetry, music and graphics — that animate, inspire and encourage people to be the active authors of their own future.

Link to SAHA Shifty Records Virtual Exhibition - Indipendent Music in the 1980's