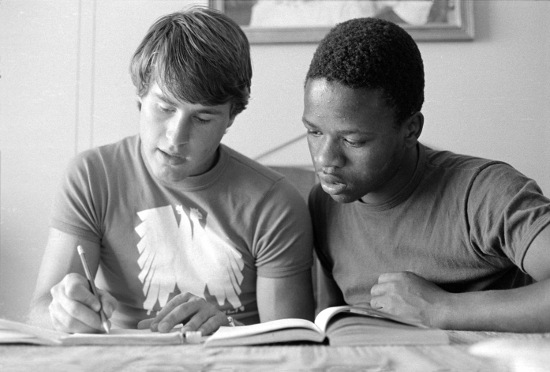

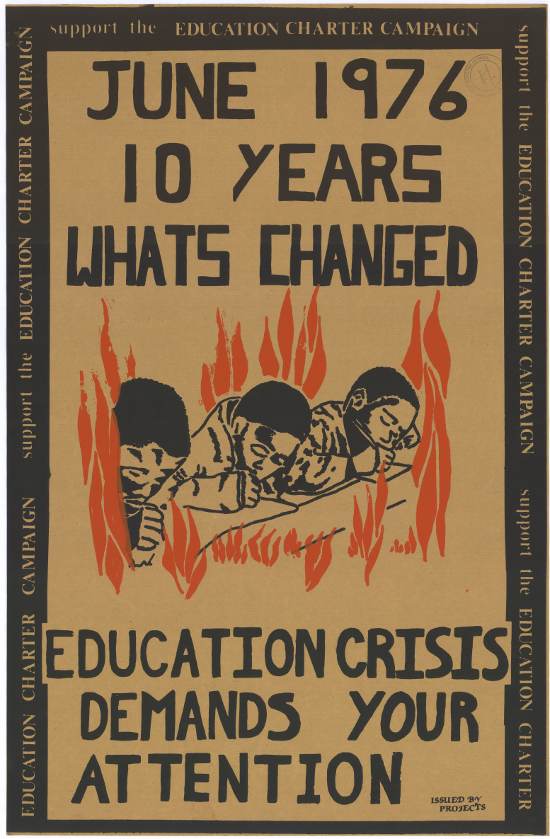

People’s Education inspired many people with its alternative vision to Bantu Education. But it also meant different things to different people. Some viewed it as a movement to improve education, while others saw it as a strategy to mobilise people politically and overthrow the government.

At the Conference, Father Smangaliso Mkatshwa explained what People’s Education was:

“…[it] prepares people for total human liberation; one which helps people to be creative, to develop a critical mind, to help people to analyse; one that prepares people for full participation in all social, political or cultural spheres of society.”

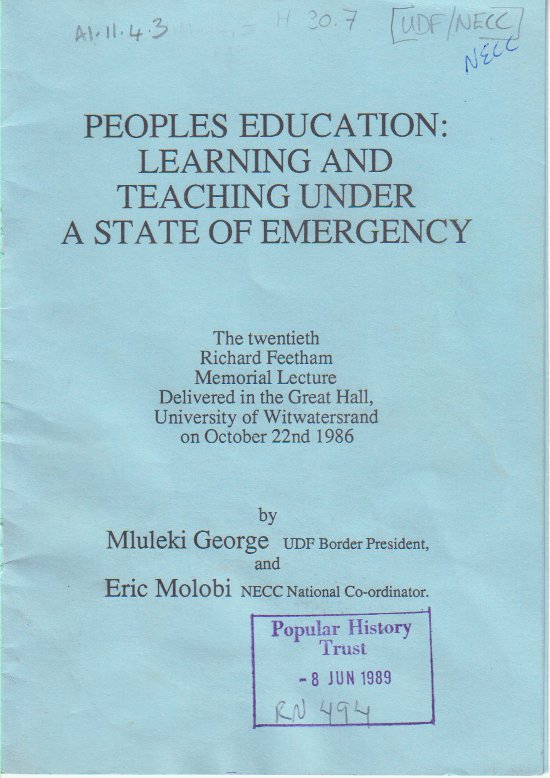

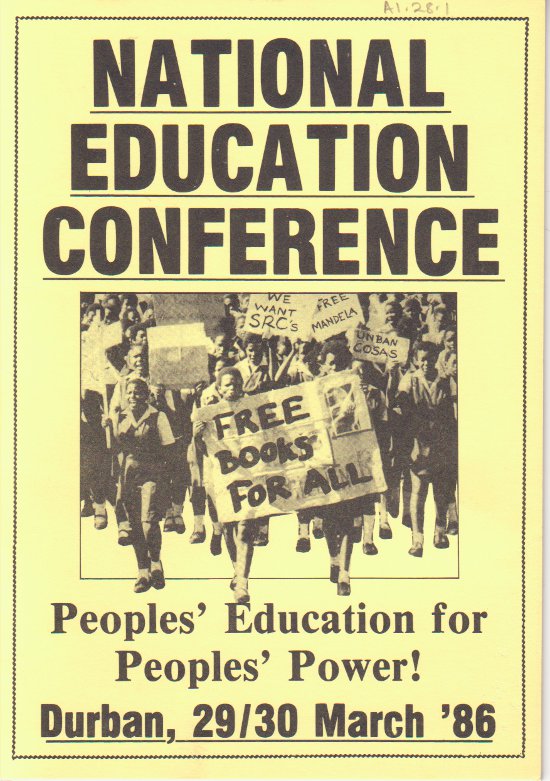

The idea of People’s Education was reinforced when the NECC met in 1986. At the heart of the campaign for People’s Education was an attempt to gain political control of education. The NECC wanted to shift the control of education from the Department of Education and Training (DET) to communities. It aimed to set up structures in communities where parents, teachers and students would work to create a better, non-racial and democratic education for all. The NECC recognised the important role of teachers in implementing People’s Education and it worked with teachers’ organisations to try to improve the strained relations that existed between students and teachers. It also established subject committees in History, English and Maths, which began creating new education materials that was not influenced by apartheid ideology.

But the NECC also believed that the state should continue to fund education by providing the necessary infrastructure to make schools work.

However, it proved difficult to negotiate with the DET, which often ignored the NECC. There was a fear of state reprisals, and in fact, many of the members of the NECC were detained or harassed, making it difficult to organise.

By 1987 students began to return to school. But clashes between police and students soon broke out, as none of the issues in education had been resolved. The government began to severely restrict the activities of the NECC. In February 1988, the NECC was banned along with the UDF and a range of other organisations. This made it very difficult for a programme of People’s Education to advance.

Exhibitions in the classroom

Reading like a historian

SOURCE:’ Fighting for the Right to Learn’, produced by Horizon Journal of the ANCYL, May/June 1991.

Read the source and answer the following questions:

- What was the Back to School Campaign that COSAS initiated?

- Why did COSAS feel there was a need for such a campaign?

- How did the Department of Education and Training hamper this campaign?

- Do you think the campaign was a success or not? Explain your answer