Julie Frederikse - September 2015

The word "mashup" didn't exist when I was reporting, researching and writing in the 1980s but that's what you could call my books today. The technology is different but the approach was the same then as it is now: to creatively combine elements from various sources to tell a story in a new way.

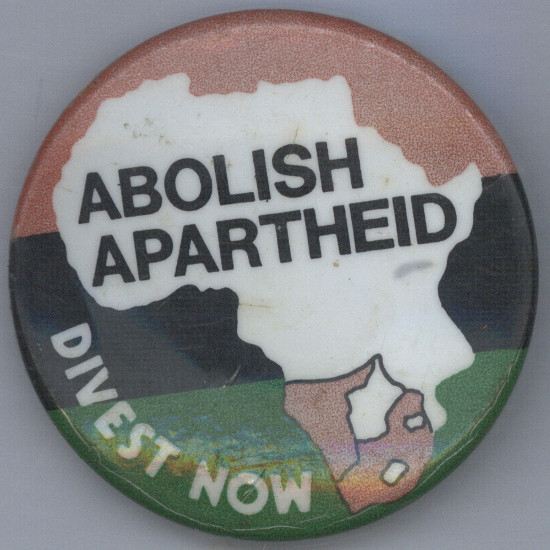

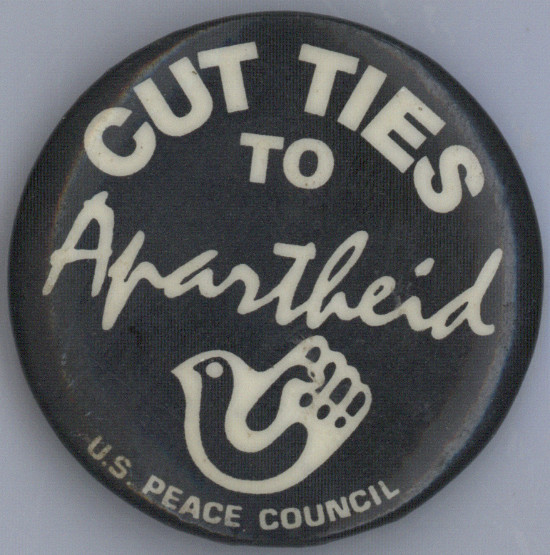

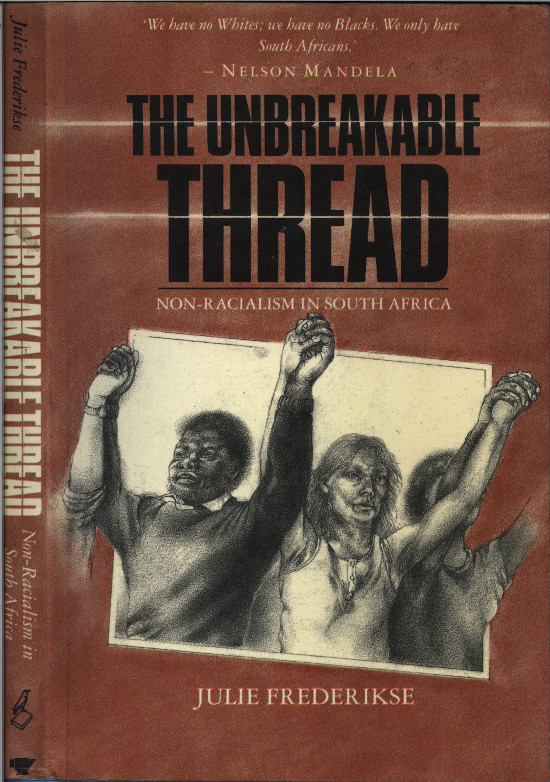

The Unbreakable Thread: Non-racialism in South Africa is a mashup of words and pictures: transcriptions of interviews, news conferences, political meetings, court cases, state radio and liberation movement broadcasts juxtaposed with photographs, newspaper cuttings, advertisements, flyers, posters, badges and stickers. In this introduction to the book's 25th anniversary digital republication I aim to chronicle the origins of this and my other southern African mashups.

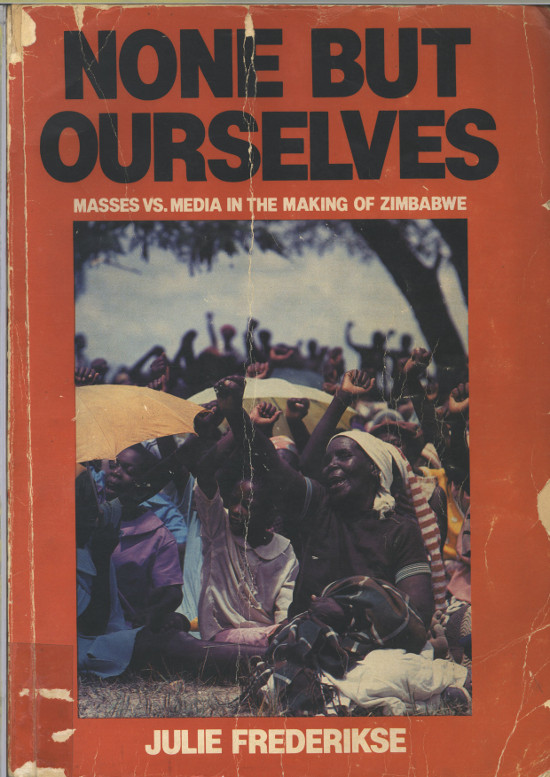

The Unbreakable Thread is part of a series of mashups that started with None But Ourselves: Masses vs Media in the Making of Zimbabwe. First published in 1982, the title is from "Redemption Song" by Bob Marley, quoting fellow Jamaican Pan-Africanist Marcus Garvey:

"Emancipate yourselves from mental slavery, none but ourselves can free our minds."

Marley was on our minds in southern Africa after he dedicated a song to Zimbabwe's liberation struggle. "Mash it up-a in-a Zimbabwe," he sang as the country moved towards independence, "Africans a-liberate Zimbabwe."

The transition to majority rule of the country named after British imperialist Cecil Rhodes was the first major story I covered as a young journalist newly arrived in Johannesburg in 1979.

I flew to Lusaka, Zambia to report for several North American and European radio news services on the Commonwealth Heads of Government meeting that focused on the ex-colony of Southern Rhodesia.

By the end of the year the Lancaster House negotiations in London had led to a plan for democratic elections and Zimbabwe's independence.

I drove from Johannesburg to Salisbury, as Harare was then known, soon after the January 1980 ceasefire that launched the election campaign. Members of the Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army (ZANLA) and the Zimbabwe People’s Revolutionary Army (ZIPRA) were assembling at points throughout the country to lay down their arms, while the Rhodesian Army was confined to barracks.

One of the first journalists I met was a Mozambican working for the state news agency and broadcaster, Carlos Cardoso. We shared an office, covering the Zimbabwe elections, from the round-up of guerrillas in military assembly points, to the campaigning and voting. It was Carlos who encouraged my idea of exploring why the landslide victory of Zimbabwe’s largest liberation movement came as such a shock to so many in southern Africa and around the world.

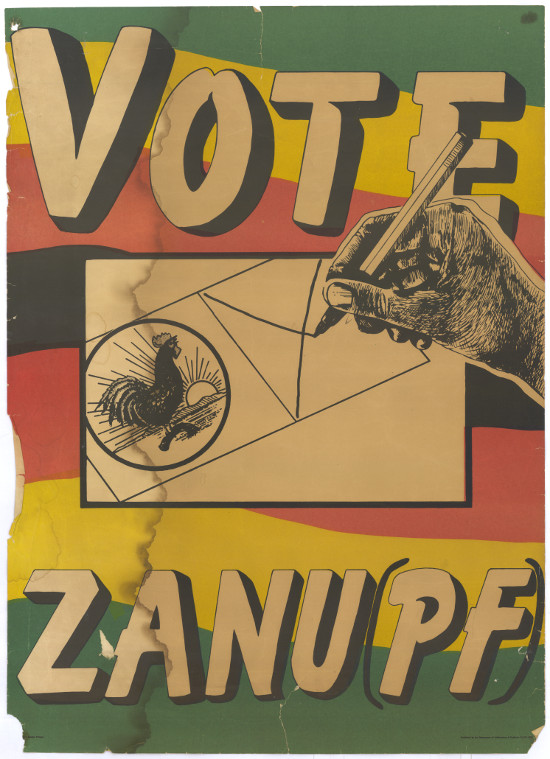

"The cock is crowing," began the entry in my journal after the election results were announced in early March of 1980. The reference was to the symbol of Mugabe's Zimbabwe African National Union-Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) party. "All over town people are flapping their arms like roosters while journalists frantically backpedal to rationalise their way off-base predictions. Euphoria, and I felt a part of it in a way - the vindication of the will of the people was exhilarating."

I had been interested in Africa long before moving to the continent. Washington DC, where I was born and grew up, had a large African-American majority and there was awareness of the injustices of apartheid. When I went to university and joined the campus radio station, my first news report was on student demands for Cornell to disinvest from South Africa.

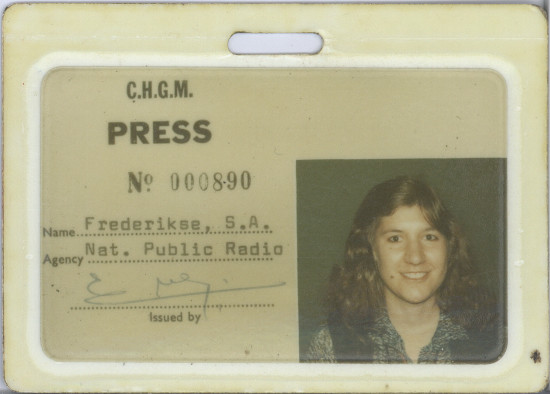

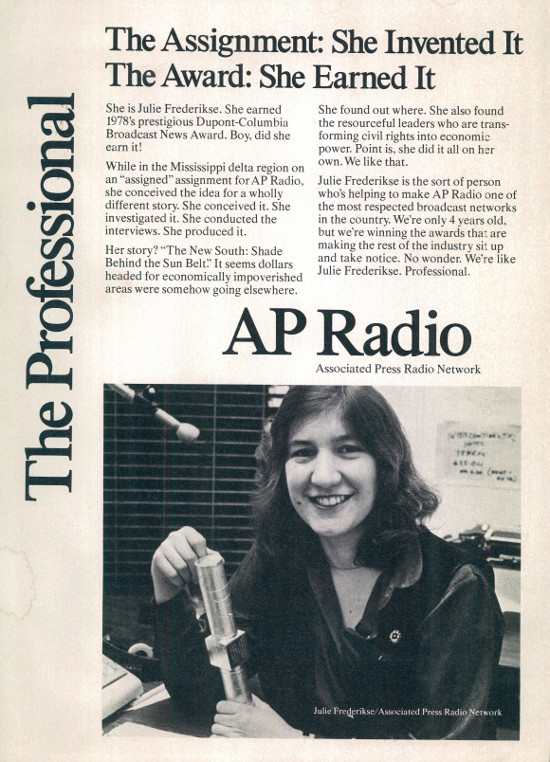

My first job after finishing university in 1975 was as a radio newscaster and reporter at NBC in New York, broadcasting from 30 Rock , now of sitcom fame. After winning the New York City Press Club award for Cub Reporter of the Year, I was offered a job with a network of Associated Press radio stations headquartered in Washington DC to produce documentaries, travelling from Appalachia to Alaska. It was a trip to Mississippi that led me to South Africa. I came to the attention of the US non-commercial broadcaster, National Public Radio (NPR), in early 1979 when a documentary I researched in the Mississippi Delta on political changes since the Voting Rights Act won a Columbia-duPont award.

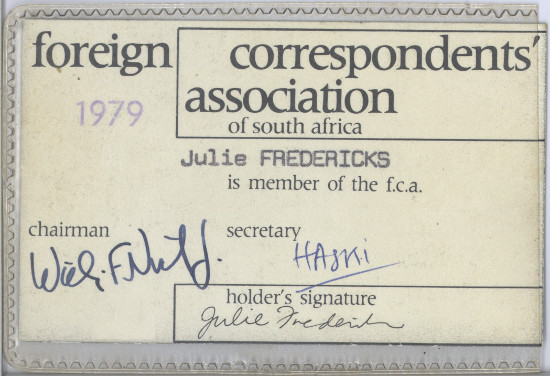

NPR had been relying on a Johannesburg-based newspaper correspondent for occasional reports who was returning to the US. In the view of many international broadcasters, newspapers and news agencies there was not enough news out of South Africa to justify a full-time correspondent so they used "stringers" who worked for more than one media outlet. I was ready to join their ranks. The problem was that the South African government gave working visas to correspondents, not stringers. Once NPR was persuaded to support my application as their purported South Africa correspondent my visa was granted.

occasional reports who was returning to the US. In the view of many international broadcasters, newspapers and news agencies there was not enough news out of South Africa to justify a full-time correspondent so they used "stringers" who worked for more than one media outlet. I was ready to join their ranks. The problem was that the South African government gave working visas to correspondents, not stringers. Once NPR was persuaded to support my application as their purported South Africa correspondent my visa was granted.

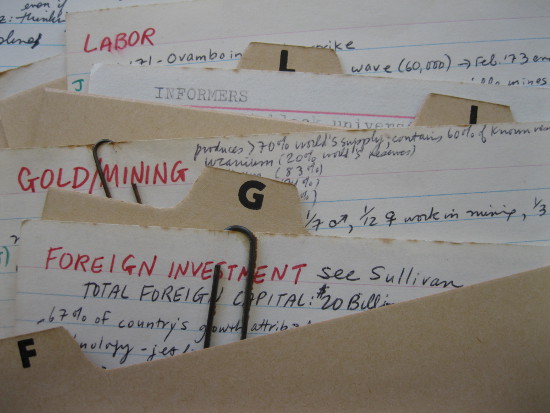

I left my job at AP Radio and spent a few weeks at in Washington's Martin Luther King Junior Memorial Library. I read books and periodicals on southern Africa, taking notes on index cards.

I left my job at AP Radio and spent a few weeks at in Washington's Martin Luther King Junior Memorial Library. I read books and periodicals on southern Africa, taking notes on index cards.

The most valuable preparation for what awaited me in Africa came from veteran journalists who reported on the continent. I was grateful that many took time to advise someone so young, unknown and naïve as I was then. I discovered one of the few US publications then dedicated to African coverage, Africa News , whose co-founders Reed Kramer and Tami Hultman had been deported from South Africa after secretly documenting the role of US companies there. Reporter Charlie Cobb was respected for his African coverage and before that, his civil rights work in Mississippi. I was invited to Africa News offices in Durham, North Carolina to see its modest but influential operation. We planned how I could file for the monthly print publication and its incipient radio service without attracting attention from the South African government.

I learned all I could from the work of lobbying groups like the American Committee on Africa (ACOA) and TransAfrica, but tried to do so without raising my profile with the South African government, whose spies reportedly monitored their offices. I met with the African National Congress (ANC) representative to the United Nations, Johnny Makhathini, but not at the UN. In Boston I met "Danny Schechter, the News Dissector" of WBCN radio, whose commitment to South Africa had begun with his recruitment to the ANC underground while studying at the London School of Economics in the 1960s. The Christian Science Monitor journalist who I would replace at NPR, June Goodwin, gave me advice about dealing with the nearly all-male Johannesburg press corps.

I was nearly ready to leave for South Africa but still seeking a few more broadcasters to report for, given that the rand was worth more than the US dollar, so the cost of living would be higher for me than at home. I contacted the Canadian Broadcasting Company, who flew me to Toronto for training in covering southern African news for the CBC.

I travelled to South Africa via Europe, stopping in Holland to see relatives and friends. I met with the head of Radio Netherlands' Africa service, Zimbabwean Stanley Nyahwa, who was keen for me to file news and feature reports from southern Africa. In London I visited the BBC, where I met top African female journalists Ofebia Quist-Arcton and Akwe Omosu, and arranged to produce occasional features for the BBC Africa service.

I did not travel alone to a continent where I knew no one with only a hope that I could make a living as a freelancer. I was relying in part on a grant I had received from the US National Endowment for the Arts to produce a radio documentary in Africa. I planned to spend a few months settling in and then begin work on this project.

My strongest memory, upon arrival in Johannesburg on a chilly June morning in 1979, is of the posters advertising the day's newspapers. One headline announced former Prime Minister John Vorster's resignation as state president following revelations of illegal funding for apartheid propaganda. Another poster told of the defeat of South Africa's self-proclaimed white world boxing champion, Kallie Knoetze, by African-American John Tate in a match held in the Bophutatswana bantustan.

I was nervous about going through airport customs and immigration in Jan Smuts Airport upon my arrival. Luckily, my little address book of South African contacts, written in an amateurish secret code, was not discovered in its hiding place. I entered South Africa and soon filed my first news story, on Vorster's resignation.

I kept a journal from the day I left for South Africa, writing detailed personal accounts of my experiences. By re-reading material I saved from that period I have been able to trace the evolution of my initial mashup, from a radio documentary into a book and audio-visual show, laying the ground for the mashups that followed. I had saved my diaries, letters and other written material since 1979. Memories fade so it is useful that, decades later, there are records to prompt, challenge and verify my recollections.

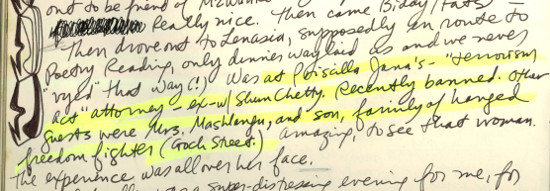

I wrote in my journal about people I was meeting, through work and socially. This journal entry was written after a dinner at human rights lawyer Priscilla Jana's house in Lenasia, where I met the mother and brother of Solomon Mahlangu, an Umkhonto we Sizwe guerrilla who had been hanged as a terrorist. I remembered the media reports of the shoot-out with police in central Johannesburg, and his speech at the gallows that made him a hero.

My journal entries also chronicled details of South African trends, and even prices. This entry was on early black mini-bus taxis: "Township version: 8-person ‘combi' or car/van, 70 cents a trip, soon to skyrocket to R1.00 because of petrol crisis".

"99% of the news in this town is fed and the major source is the government," I was told by a veteran reporter at the offices in Johannesburg's city centre where most foreign correspondents worked. I did not rely on the telex service used by the print journalists so I decided to save on office rent and work from home.

told by a veteran reporter at the offices in Johannesburg's city centre where most foreign correspondents worked. I did not rely on the telex service used by the print journalists so I decided to save on office rent and work from home.

I could simply unscrew the mouthpiece of the phone in my flat and attach "crocodile clips" ("alligator clips" in North America) to send audio reports from my tape recorder down the phone line to Washington, Toronto, London and Hilversum, Holland. I edited radio reports in my makeshift studio using razor blades and splicing tape to cut recording tape on reels. I sent news reports and features by courier, or asked people flying to Europe or the US to carry the tapes.

Before I left for Johannesburg I received a letter fromthe South African Foreign Correspondents Association in response to my questions as to where I might rent accommodation. They advised that although newly arrived journalists routinely stayed in centrally located Hillbrow, crime was on the rise so the northern suburbs might be a better choice. To me, Hillbrow was the most cosmopolitan place in Joburg, and in places like Estoril bookshop, Café Wien and Fontanas all-night supermarket, the least racially segregated.

I found a flat to rent in Hillbrow and soon discovered that black people were living in my building. They were protected from police raids by the white caretaker, a one-time socialite whose face and hands had been horribly scarred in a fire. "We move in a multi-racial crowd," she told me, "Every gay, every whore, every sex change is welcome here, there's nowhere else for them to go in this screwed-up city."

I learned that there was a club in the basement of the building across from my flat. The music was live and the audiences racially mixed.

One of my first in-depth radio features was on South African literature so I visited Ravan Press, which was publishing emerging black writers, as well as early work by authors J.M. Coetzee and Nadine Gordimer. As I was finishing my interview with managing editor Mike Kirkwood, he had to handle a crisis. A group of writers for the often banned township literary magazine Staffrider was travelling to Cape Town for an arts conference and they needed someone to help with the driving. Did I have a valid driver's license?

The next day I was at the wheel of a van headed south. Passengers included writers and poets Matsemela Manaka, Mafika Gwala, Muthobi Mutloatse, Mtutuzeli Matshoba, Jaki Seroke, Ingoapele Madingoane, Neil Williams and Masilo Rabothata, as well as visual artist Mzwakhe Nhlabatsi. The only woman writer in the group was Miriam Tladi, South Africa's first black female novelist.

I didn't wait long to start contacting the people whose numbers were in the little notebook I had compiled before arriving in South Africa. Some of them had been detained and banned, like the first people I met: journalist Enoch Duma, Methodist minister Cedric Mayson and his wife, Penelope. I visited the writers I had met on that road trip to Cape Town at their homes in Soweto and they took me to readings where they performed their work. One of the few young women among the emerging writers was Gcina Mhlope, recently arrived from Transkei. I gave her lifts back to her room at the women's hostel in Alexandra township and we became friends.

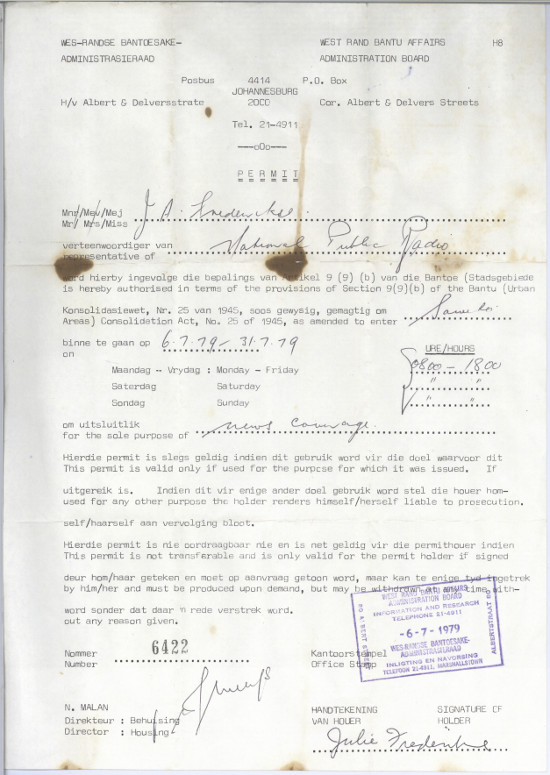

Whites had to get a permit from the West Rand Bantu Affairs Administration Board in order to legally visit black townships, always an ordeal for me as the process involved a lecherous bureaucrat. Although my permit stated it was "for the sole purpose of news coverage" I visited friends and went to parties in townships. The danger then was less from crime than police road blocks. I saw the inside of the notorious John Vorster Square police headquarters after being stopped driving out of Soweto and taken there for questioning.

Many of the white friends I made came from student left and activist religious backgrounds. Some worked for community and labour organisations. They didn't live in the northern suburbs where most foreign correspondents stayed, but in areas like Yeoville, Berea and Crown Mines.

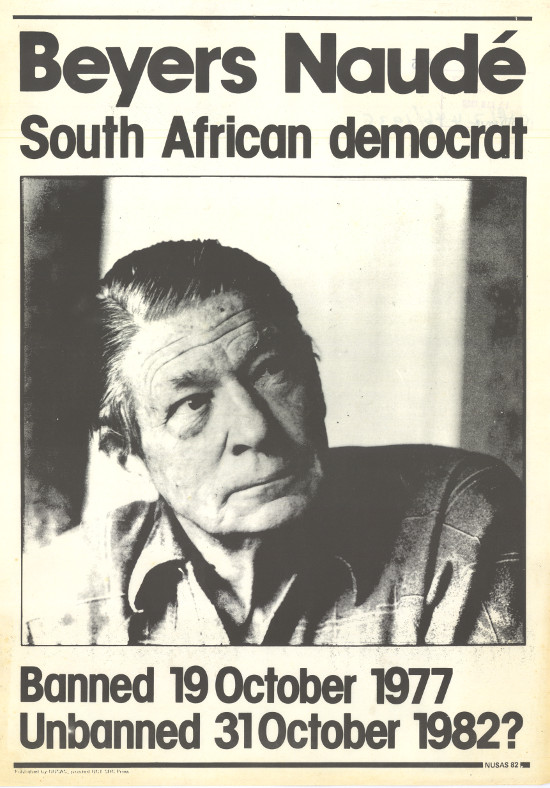

One of the names in my little book of contacts was of Dutch Reformed Church minister Beyers Naude. "You must speak to the old man," I kept being told - to my amazement by young Black Consciousness Movement supporters. So i went to meet the Afrikaner who had quit the Broederbond to oppose apartheid, then aged 64. Banned, he was under Security Branch surveillance. I was told to park around the corner as if going to nearby Zoo Lake, and not to knock at the front door.

"The most solace-giving space I've yet found here must be Beyers's garden," I wrote in my journal. Knowing how keenly South Africans were following developments in Zimbabwe, Beyers and I discussed the effect its political changes might have on South Africa. I had a feeling that my idea was bigger than just a radio documentary, and that I should use visual material as well as audio. "Had a good talk this week with Beyers and he's really keen for my stuff to ‘get out'", I wrote upon my return to Johannesburg in late March 1980. "I am feeling charged up about the Zimbabwe media project, thinking of a slide-tape show" (an audio-visual presentation using photos projected as slides, accompanied by synchronised audio).

When I learned that records of the Rhodesian government were being secretly shredded and burned, I realised what a contribution it would be to save the material I had, and to collect more. I aimed to conduct interviews about media in the Zimbabwean liberation struggle and wanted to do this while memories were fresh.

I made plans to go back to Zimbabwe for the April 1980 independence celebrations with two South African photographers, Paul Weinberg and Biddy Partridge. We drove up together to conduct interviews and shoot photographs for the planned audio-visual show. Paul stayed in Harare and photographed Mugabe and Marley at Rufaro Stadium as the Union Jack was lowered and the new Zimbabwe flag raised. Biddy and I travelled to rural celebrations, where I conducted interviews and she took photographs.

with two South African photographers, Paul Weinberg and Biddy Partridge. We drove up together to conduct interviews and shoot photographs for the planned audio-visual show. Paul stayed in Harare and photographed Mugabe and Marley at Rufaro Stadium as the Union Jack was lowered and the new Zimbabwe flag raised. Biddy and I travelled to rural celebrations, where I conducted interviews and she took photographs.

Carlos Cardoso came from Maputo to cover Zimbabwe's independence. He was due to take up a new post as editor of the Mozambican news agency, AIM. He insisted we meet privately and gave me a stern lecture on what he saw as looming security issues for me in South Africa. He spoke from personal experience, having been detained by South African Security Police in 1975 while a student at the University of the Witwatersrand, and deported in the run-up to Mozambique's independence from Portugal.

"Your file is this thick! I know, I hear who you've been talking with and seeing," he reprimanded me and I later wrote in my journal. "It's no good you being booted out like I was. You must stay on - not to produce now, but later, at an opportune moment." I took his words to heart, to protect myself and my material. Another warning came from Zimbabwean activist and photographer Kate McCalman, recently returned from exile in the UK, who recounted chilling experiences with South African Security Police.

Over the next two years I made many trips from South Africa to Zimbabwe and back in my Mazda 323. I was amassing a large collection of audio recordings: interviews, media conferences, political rallies, state radio news reports, liberation movement radio broadcasts, performances of music and poetry. I was also collecting newspaper and magazine clippings, protest and propaganda leaflets, posters, badges, stickers, ads and T-shirts, while Biddy took more photographs.

I was determined to locate documentation to confirm what I was learning about the policies and conduct of the Rhodesian government. So much was similar to, and had often been in collusion with, the apartheid regime.

The caretaker of the flat where I stayed while in Harare, as Salisbury was renamed, offered to introduce me to a fellow American. I wasn't particularly interested until I found out he was a mercenary who had fought for the Rhodesian army, recruited by an ad in . Soldier of Fortune magazine. I then felt it my duty to interview him, and filed an article for Africa News.

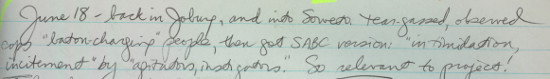

Returning from newly independent Zimbabwe to South Africa, still under apartheid, was always a jolt - even more so when I witnessed the police response to resistance. I covered a commemoration of the June 16th 1976 student uprising at Soweto's Regina Mundi Church, as I had soon after my arrival in Johannesburg a year before. This time the protest, amid heavy police protest, had greater impact on me.

Black South Africans and progressive whites were excited about their newly liberated northern neighbour. Some travelled to Zimbabwe just to experience majority rule. Others went to join the ANC underground. Beyers Naude felt strongly about the need for South Africans to learn about the ill-fated propaganda war the Rhodesians had fought to maintain white power. We decided that the focus of my work would be on ordinary Zimbabweans and the media they used to fight repression in the face of censorship.

Our challenge was to figure out how this story could reach South Africans when the media was so tightly controlled. The government did not even allow TV broadcasts until 1976. Since my radio documentary would not likely be broadcast in South Africa, Beyers believed that I should write a book. He had a publisher in mind, Ravan Press, which he had co-founded.

By mid-1980 discussions with Beyers Naude no longer took place at his house. To avoid surveillance, I would receive word to meet him at a flat that his friends made available. Since I had by then used most of my grant funding, with the remainder earmarked for producing the radio documentary, Beyers suggested the possibility of grant funding to support the writing of a book. He asked me to write a proposal to cover costs of having the recordings transcribed, travel to and from Zimbabwe, more photographs, and for the book's design and lay-out. Author's royalties would be donated to lower the selling price.

I got the news that the grant had been approved when Beyers handed me a brown paper bag that, to my astonishment, was full of cash. Subsequent funding tranches were also delivered this way. By banning Beyers the regime had forced him underground. Anti-apartheid organisations like International Defence and Aid (IDAF) figured out ways to get money to him and he dispersed the funds to approved projects.

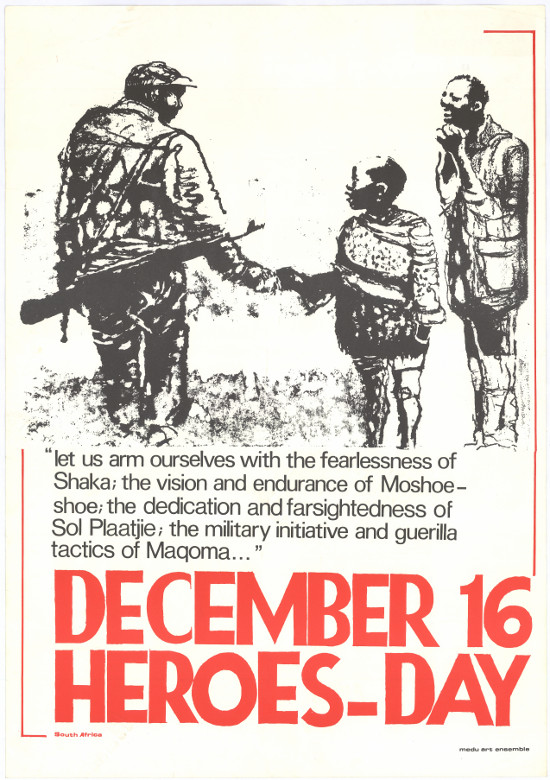

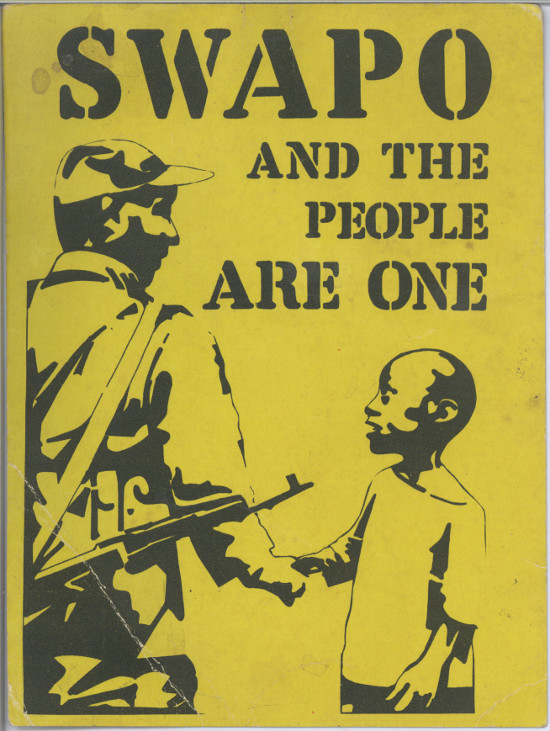

This period of further research was well timed, for in the heady months after independence Zimbabweans were interested in reflecting on the role of media in their struggle. The ZANU-PF Publicity and Information Department opened its archive to me: boxes of photographs and Super-8 mm films shot in Mozambique, Tanzania, Zambia and Ethiopia. Many photos were out of focus and poorly developed, but there were some historic images of guerrillas in the field. One photo I unearthed deserves the overused label "iconic". It shows a uniformed ZANLA fighter in the bush, his AK slung over his shoulder, shaking the hand of a young boy as an older man looks on, with both peasants gazing at the guerrilla in adulation.

By mid-1981 I was planning how to integrate words of this story, of the masses versus the mainstream media in the liberation of Zimbabwe, with the visual material. After meeting Mike Kirkwood and confirming the book's publication by Ravan Press, the deadline for the final manuscript was set: October 1981. I had not been back to the US to see my family in more than two years so my mother decided to pay me a visit in South Africa. In September we travelled together to Cape Town where she, a professional artist, painted while I did reporting.

We then drove to Cape Point. My mother was at her easel, thrilled to be painting at Africa's southernmost tip, and I was seated just beyond her, proofreading my manuscript. She watched in horror as a big male baboon started moving towards me. I didn't realise he was there until I looked up and saw him reach out - and grab those precious pages had typed and retyped over several months, with my recent handwritten corrections mae in pen and Tipp-Ex. What happened next was motivated purely by the fact that there was no back-up copy. I held on tight and somehow stared down that baboon until he finally let go of my manuscript and ran off.

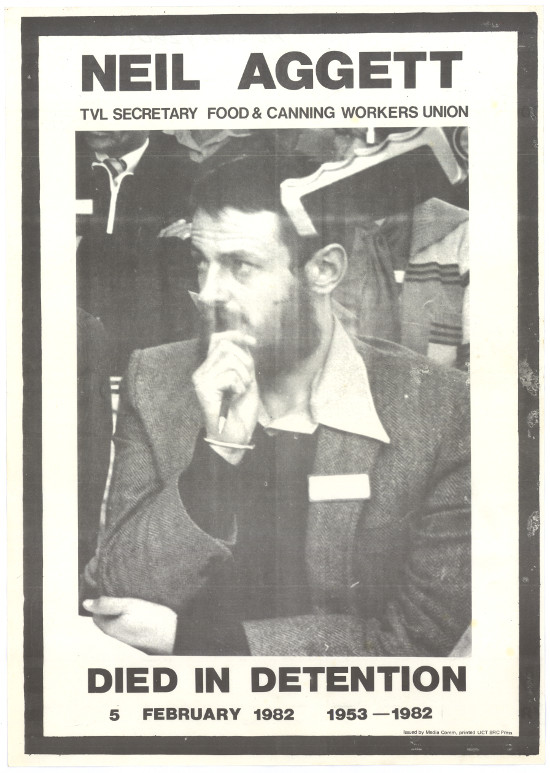

In late 1981 the security police swooped on political activists, and friends of mine were among those awoken in the early hours of the morning and detained in solitary confinement. In February 1982 I was woken at dawn by friends of detained unionist Dr Neil Aggett who had come to tell another close friend, then staying in the same house as me, that he had been found dead in his cell after more than 60 hours of interrogation.

In late 1981 the security police swooped on political activists, and friends of mine were among those awoken in the early hours of the morning and detained in solitary confinement. In February 1982 I was woken at dawn by friends of detained unionist Dr Neil Aggett who had come to tell another close friend, then staying in the same house as me, that he had been found dead in his cell after more than 60 hours of interrogation.

The increasing state represssion not only caused concern for the welfare of my friends, but also affected my work as a foreign journalist. I experienced difficulties in getting my visa renewed and the police refused to issue me a new press card. Their reasons were conveyed to me by the Foreign Correspondents Association: "extramural activities", "network of subversives", "negative reporting" and "across the colour bar".

To keep a low profile, once the editing of the manuscript was finished, the book was not laid out at Ravan's offices. Instead, graphic designer Andy Mason worked at my house. We listened to Bob Marley and hung a sign over his light table with a quote from Redemption Song: "We got to fulfill da book." None but ourselves: masses vs media in the making of Zimbabwea, a large format 368-page book, was published in September 1982. The print run of 5,000 sold out in six months and Ravan printed a second edition.

The book had reached South Africans but it was obviously important for Zimbabweans too. Zimbabwe Publishing House (ZPH), founded by veteran British journalist David Martin and Canadian Phyllis Johnson, published the book in Harare in 1983.

The UK edition was by Heinemann, one of the last titles James Currey oversaw before the company was sold and the Heinemann African Writers series he pioneered with Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe shut down. As for the US edition, Mike Kirkwood read me a letter from the Editorial Director of Viking-Penguin: "This is an extraordinary book - it seems to me quite unique. As you can imagine, it won't be easy selling this book in America, but we'd like to give it a whirl."

Penguin was persuaded, along with Heinemann, to do a joint print run in Harare, together with the reprints for ZPH and Ravan, printed on local paper. Heinemann's imprint already had "London Ibadan Nairobi" on the spine, but it was a first for Penguin to receive books printed in Africa. The US edition sold out when the Association of Concerned African Scholars (ACAS) helped university libraries order copies. I later met American students in Harare who said that reading None But Ourselves had sparked their interest in southern Africa. The total print run in Africa, Europe and North America from 1982-84 was approximately 20,000.

The None But Ourselves audio-visual show was produced with Africa News. It premiered at London's Africa Centre in December 1983,introduced by Oxford Professor Terence Ranger, and was shown widely in Zimbabwe. The show's first premiere was at the first conference of the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) in 1985. Copies were distributed in South Africa by the National Education Union of South Africa (NEUSA) resource centre. The radio documentary was broadcast on US public radio stations.

Here is an interesting example of the influence of None But Ourselves. After selecting the iconic photo of the guerrilla with rural supporters from the ZANU-PF archives for publication in the book, I saw the same photo rendered as a drawing on an Umkhonto we Sizwe poster. I later spotted another version of the same image on a card supporting the Southwest African People's Organisation (SWAPO): the guerrillas had become Namibian.

I cannot pinpoint the precise moment when my next book was planned, in a similar mashup format. This one would be on South Africa's multi-faceted liberation struggle, a contrast to Zimbabwe's mainly rural war. I had been conducting interviews and collecting material from a wide range of sources all over South Africa, from opposition groups to government, including media of both. I was encouraged to use the material for another book, not only by Beyers Naude and Mike Kirkwood, but by political activists who knew of my interviews and sometimes asked to listen to my tapes.

In late 1982 my trouble with South African visas and accreditation led to my leaving Johannesburg to resettle in Harare. I applied to the South African government for a vsa to return to do reporting and was granted two short-term visas, coinciding with the government's desire for media coverage. So I travelled to South Africa in late 1983, ostensibly to cover the whites-only referendum to approve the new tricameral parliament, still white-dominated and without African participation, but open to coloureds and Indians. I later got a short-term visa to cover Prime Minister PW Botha's 1985 "Rubicon speech", when he was expected to announce major political reforms but did not.

During these visits to South Africa, I showed up at the requisite state-run media events and press conferences but mainly used my temporary work permits to conduct interviews and collect material for my new book project. In 1985 I travelled from Harare to Johannesburg, Durban and Pietermaritzburg to do what I believed would be my last interviews inside the country for a while.

I also conducted interviews in Nelspruit, where I met secretly with Mathews Phosa, then working as an underground MK operative (and used a pseudonym to protect his identity when the interview was published in Africa News). I went to the township of KaNyamazane (meaning "place of the animals") to interview homeland leader Enos Mabuza about his openness to the ANC.

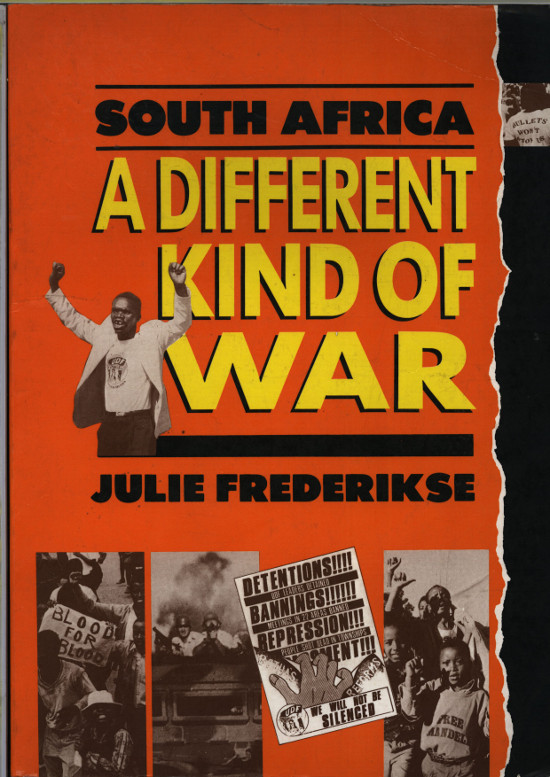

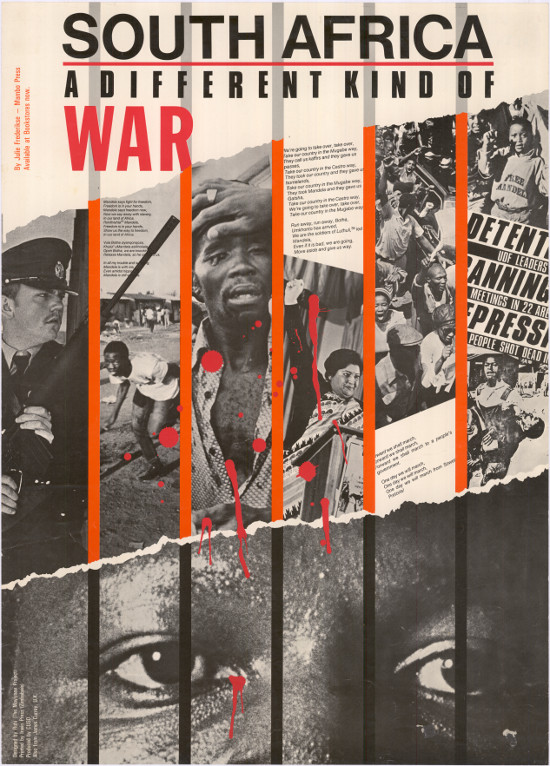

Mashup Number 2 was South Africa: A Different Kind of War, published by Ravan Presss in South Africa to mark the 10th anniversary of the June 16th 1976 Soweto uprising. The design, much like that of None But Ourselves on Zimbabwe, was described by a reviewer as "a documentary form that combines the reflective depth of print with the swift movement and pictorial variety of film". The US publisher was Boston-based Beacon Press, who joined in donating a portion of the income from sales of the book to families of South African political prisoners (via ACOA).

The UK edition was by James Currey's publishing house of works from and about Africa. The Zimbabwe edition was by Mambo Press, a Catholic mission-based publisher once banned by the Rhodesian regime and relaunched after independence. A German translation was published by the Southern African Information Centre. Ravan reprinted its edition of the book in 1987.

Mashup Number 3 focused on the history of non-racialism in South Africa, an issue I was encouraged to research by blacks and whites, inside the country and in exile. I had first been struck by a South African debate around race and class at a 1979 Media Workers of South Africa (MWASA) conference, when I was surprised by a call from former Black Consciousness supporters amended a resolution to refer to a "worker" instead of "black worker".

I questioned Beyers Naude as to whether or not there was a role for white people: "A white person should learn that the contribution he can make to the struggle for liberation can only be a complimentary one," was his reply. "A white should be willing to offer his skills, experience and knowledge but the initiative for change, the real steps to be taken, must come from the black community."

After 1985 I was refused further visas to South Africa. I still had ties with friends and contacts in the country, many of whom often travelled to Zimbabwe, and I exchanged letters with others. I felt a bond with those who were imprisoned for fighting apartheid for I had been granted a prison visit to Barbara Hogan when she was detained in The Fort women's jail in Hillbrow, awaiting trial in 1982. After she was sentenced to 10 years in prison for treason, for supporting the ANC, I was on her list, as well as that of another political prisoner, Rob Adam, of those who could send birthday and Christmas cards to them in jail.

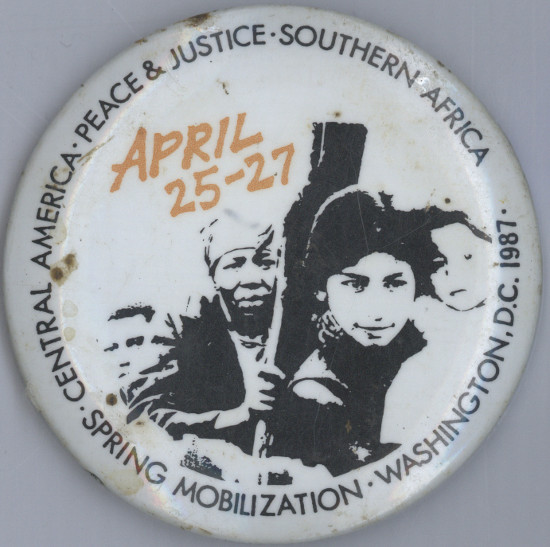

Since I was longer able to conduct interviews inside South Africa, from 1986-89 I interviewed South Africans in Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Zambia, Tanzania and Kenya, and in the UK, US and Canada.

It may be useful to recall the technology behind the audio recording and transcription of my interviews. I recorded two copies of each interview on an audiotape-recorder and stored the cassettes separately. A notebook I had used in conducting interviews in the UK in 1986 contained not only questions for interviewees, but also a shopping list of items not easily found in Zimbabwe at that time, including an electronic typewriter ribbon and correct-tape because the interviews were transcribed on paper, making carbon copies.

After the publication of None But Ourselves: Masses vs Media in the Making of ZImbabwe, I donated the material collected in my research to the Zimbabwe National Archives. I wondered what should happen to the material collected for my books on South Africa. The growing collection was intended to be returned to the country when it was free, but how should the material be organised and maintained until then?

These concerns in the mid-1980s, while I was living and working in Harare, led me to seek funding to store, catalogue and preserve the recorded interviews and other material I already had, as well as support for further interviews for a new book I was planning. Potential donors asked that I send letters of support for the project.

The project was granted funding by three Dutch non-governmental organisations and the Popular History Trust (PHT) was founded in Harare in 1987. Thus began the process of cataloguing the core collection of South African documents, posters, flyers, stickers and badges, and its expansion.

The transcribing of interviews continued, the tapes and transcripts were organised, and additional interviews were conducted. A relationship with Afrapix, a South African photographers collective, was formalised, and CUSO of Canada funded the development of a computerised database. South African activist Derek Hanekom joined as PHT's coordinator upon his release from prison in Pretoria for supporting the ANC. He helped arrange for United Democratic Front (UDF) and COSATU-affiliated organisations to donate documents, posters and flyers to PHT, and to find ways of getting the material to Harare for preservation.

Mashup 3 was The Unbreakable Thread: Non-racialism in South Africa. It was initially planned as another co-production with James Currey, but his imprint was focusing on academic works on and from Africa, so he and Zed Books editor John Daniel agreed that Zed should publish the UK edition. The book was designed by Zed in London, with the film for printing sent to southern Africa.

On the morning of the 2nd of February 1990 the PHT staff gathered around a radio to listen to the South African President's speech at the opening of Parliament. Word was that FW de Klerk would say something significant. Our office in Harare's Avenues were at that point protected by armed guards, after several nearby bombings of people and places regarded by Pretoria as ANC targets. De Klerk's speech was indeed historic, as he announced the immediate unbanning of the ANC and the planned release of Nelson Mandela.

The Unbreakable Thread: Non-racialism in South Africa was published in late 1990 by Ravan Press in South Africa, Anvil Press in Zimbabwe, Zed Books in the UK, and Indiana University Press in the US. The PHT collection, with all its primary source material, was transferred from Harare to the South African History Archive (SAHA) in Johannesburg. I could not attend the South African launch of my book because the first applications for visas for myself and my children to re-enter South Africa were denied by what was then still the old guard at the Harare consulate.

Although I was keen to get back to South Africa, I appreciated the time I had todisengage with the country that had been my family's home for eight years. To mark the 10th anniversary of Zimbabwe's independence I worked with Anvil Press founder Paul Brickhill on a reprint of None But Ourselves: Masses vs Media in the Making of Zimbabwe. Together with the Oral Traditions Association of Zimbabwe we launched the None But Ourselves Oral History Project, supported by Zimbabwe's Minister of Education Fay Chung, with books distributed to government schools.

Included in this new edition of the book was a list of suggested questions to use in conducting interviews with Zimbabweans who had been part of their country's liberation war, known in Shona as Chimurenga. The idea was to sit down and talk to military veterans as well as men and women who secretly supported the guerillas, plus relatives and friends, people living in rural areas where the war was fought, those who lived in the cities and townships, returned exiles, and any others who might be selected for interviewing. The competition was aimed at high school history students, with a category for adults to enter as well.

While in Harare throughout 1990, waiting for a visa to enter South Africa, I had time to reflect on Beyers Naude's idea, ten years before, that South Africans could learn from Zimbabwe's history. I wondered if its post-independence period might also offer lessons for young South Africans in their country's upcoming transition to non-racial democracy. So I started interviewing Zimbabwean children and teenagers about their experiences of race and class integration in schools from 1980-90, with a view to writing a book.

These interviews with young Zimbabweans showed that a divide still existed in the country, but that it was less about race than class. The gap was between two groups. There were those called the Nose Brigade, a derogatory term for black children at racially and economically mixed schools in the urban areas who were said to speak English "through their noses" like snobs. The other grouping was known as VSRB, for Very Strong Rural Background, meaning the majority of poor Zimbabweans who attended rural schools.

At the end of 1990, after negotiations between the South African government and the ANC had begun, my children and I were granted visas. We moved to South Africa in time for the new school term in 1991. The kids were a bit nervous about the odd racial balance they had heard about in South Africa's newly integrated "Model C" schools, with a majority of whites among both children and teachers. Our 7-year-old daughter marveled at what it would be like in South Africa: "A white teacher? I've never seen one of those!" I was granted Permanent Residence as a spouse of a returnee under the historic Groote Schuur Minute signed between Mandela and de Klerk, and became a South African citizen.

My first job after returning to South Africa was at the Education Policy Unit (EPU) of the University of Natal, to write a book on schools integration based on my interviews with young Zimbabweans. All Schools for All Children was published by EPU and Oxford University Press South Africa in 1993.

Returning to South Africa after Mandela's release was exciting but also at times traumatic, given that the period of 1990-94 was more violent than any previous period in the country's history. One incident during those tense times proved resonant for me: the explosion of a bomb at a high school in Nelspruit, in Mpumalanga. The attack was suspected to be the work of racists opposed to schools integration, and the Truth Commission later confirmed that it was planted by Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging (AWB) supporters. My husband had attended that school in the town which I knew well from family visits.

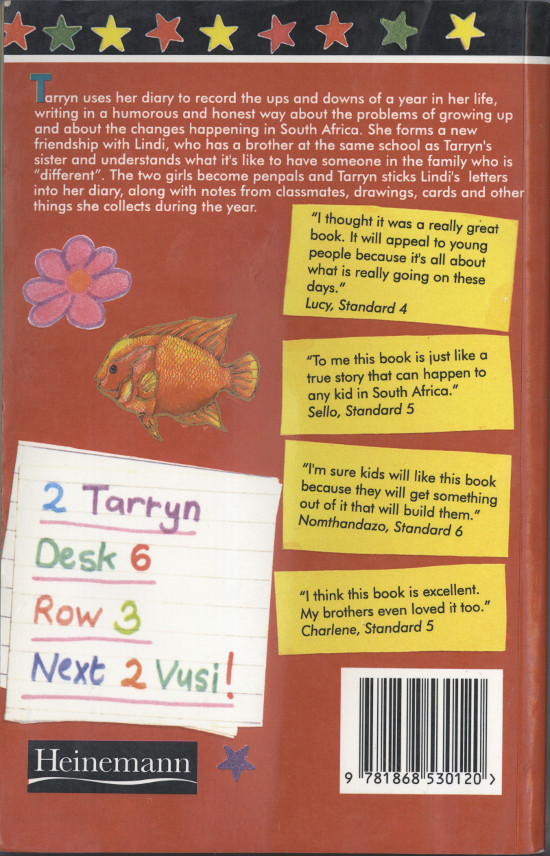

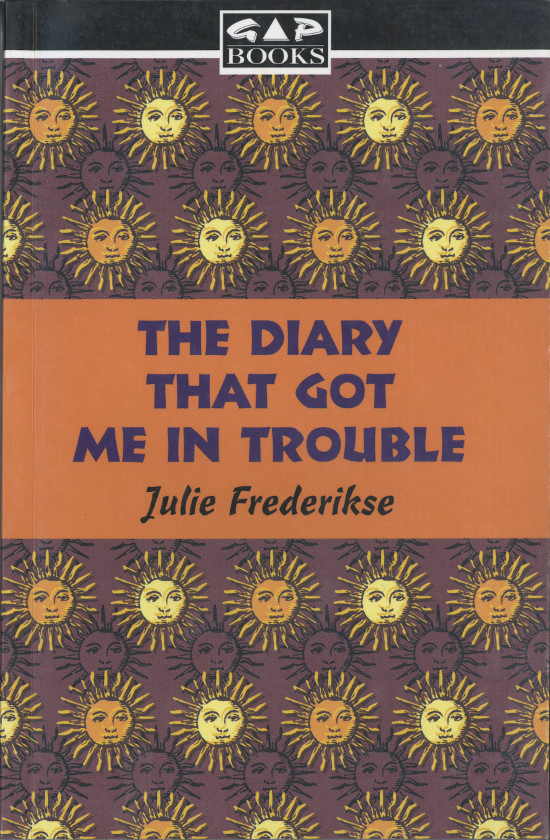

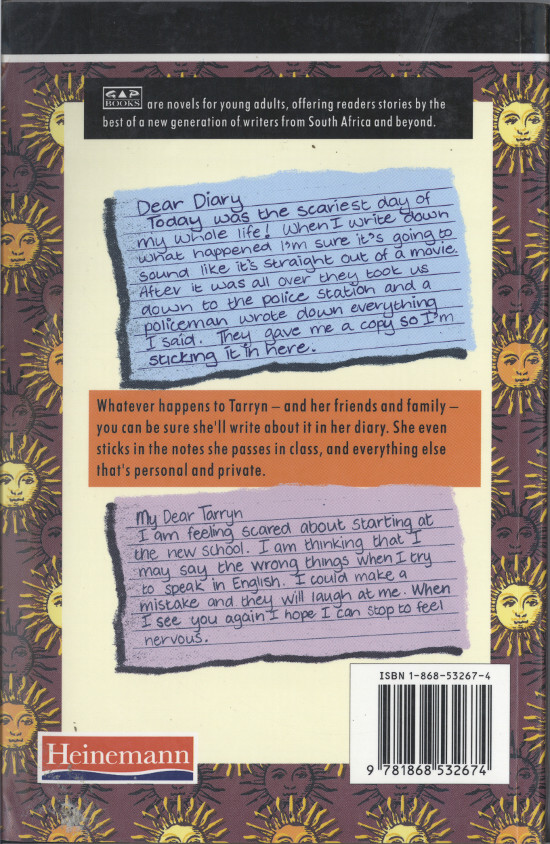

I was inspired to write a novel for young people set in a semi-rural South African town during the upheaval of the early 1990s. Told from a child's point of view, the story included a fictionalised version of the school bombing. While visiting from Mozambique, Carlos Cardoso read the manuscript of the novel for he was curious about the changes in the area where he had been sent to boarding school as a teenager from Maputo (then Laurenco Marques) and he gave the book its title.

Reflecting 25 years later on The Unbreakable Thread and my other mashups, I am proud to have been part of founding SAHA and donating my materials to the collection. My own passion for oral history grew from my radio work. I admired the ability to ask good questions and listen, and explored ways to make ordinary people’s words come alive to others, sometimes supported by visual material. I had been influenced by books like A Seventh Man on European migrants by John Berger and photographer Jean Mohr, by Let Us Now Praise Famous Men on sharecroppers during the US Depression by James Agee and Walker Evans, and by the many works of radio host and oral historian Studs Terkel.

“It can happen that a book, unlike its authors, grows younger as the years pass,” was Berger’s comment when A Seventh Man was hailed as still relevant four decades after its publication. The people who were part of my southern African mashups have gotten older and some have passed away, but I hope that the books themselves may “grow younger” by sparking interest in mashing up words and pictures to tell southern African stories, now using digital technology. Berger commented that the internet, like the language of images, “possesses the same duality of possibilities, one opposed to the other, as both an instrument of control by the forces that govern the world – that’s to say, financial capitalism and what I call ‘economic fascism’ – but also for democracy, associating directly with one another, responding in a spontaneous but collective way”.

Mashup is not the only 21st century word you could use in connection with my three 20th century books. Another is “curate”. The word is not new, but in the past a curator might have made you think of a museum professional or one who selected art for exhibition. Now you could say that what I was doing in the 1980s was curating. Academics traditionally described what was being curated as primary source material. Now material is curated on the internet by people with little or no training and is called “content”.

When I first started curating, before I knew to call it that, the material I was collecting was sometimes referred to as “ephemera”. This was because it was not intended to last. Anything on paper needed to make an impact soon after it was printed, as it was expected to deteriorate over time. Most of what I collected in the 1980s was on paper: newspapers, magazines, documents, newsletters, flyers, pamphlets, advertisements, cards, posters and stickers. SAHA, like most archives around the world, curates material that is both digital and “hard copy’, i.e. paper. This may change as more time is spent online and increasingly less material is printed.

It tends to be older people who retain a fondness for paper. I got emotional when I recently found a copy of South Africa: A Different Kind of War in Ike’s Bookshop in Durban. I got even more excited by the inscription hand-written on the inside cover, dated 1987 and quoting a young activist: “I think of liberation every day.” I doubt that I would have felt so moved if I had seen those words on a screen and had not held the book in my own hands.

Digital technology has made many things more accessible, including curation. Today anyone can be a curator: just photograph or scan something and share it. Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Wordpress and Storify are some of many tools for curating content on the internet. Aggregating sources, a key aspect of curation, can be performed by humans, or by algorithms of search engines, even a combination of both. Digital distribution means delivering content instantly and constantly, with potential interaction from contributors, collaborating to create more content.

Sharing curated material online reaches audiences who are both consumers and producers, so others may in turn curate and share what you have curated. Your content can be used to create more content and User Generated Content (UGC) can be curated. Websites can “crowdsource” information through open calls to users to voluntarily perform curation, aggregation, verification and dissemination.

Oral history has survived into the digital age and is being changed by it. On the internet the concept of oral history may need further interrogation. Since more people now text than talk, is texting part of an evolving oral tradition? Does the collection of online comments, messages and Tweets qualify as the curation of mini-oral histories?

Saving and sharing material – whether written, audio, visual or audio-visual – can not only tell a story but prove it true. Thus curating can be a way of bearing witness. The Swahili word for “testimony” or “witness”, Ushahidi, is the name of a map-based website mashup developed in Kenya that collects and maps information from witnesses of conflict. With such tools anyone, from journalists and historians to activists and aid workers, can offer eyewitness accounts that can be verified by returning to original sources.

I am sometimes disappointed by the fact that the steady expansion of connectivity throughout the world seems to be driving personal and individual identities rather than forging a collective identity. Another problematic phenomenon brought by the net and social media is known as the Filter Bubble. Challenging opinions can be filtered out and existing views reinforced. I wonder if and how these trends are affecting current debates, e.g. about the thread of non-racialism running through South Africa’s history and other discussions of race and class. Revisiting my southern African mashups curated in the 1980s has enthused me about new ways that such debates can be conducted today. With a huge range of accessible source material we can now connect and co-curate material with people all over our country, our continent and the world.

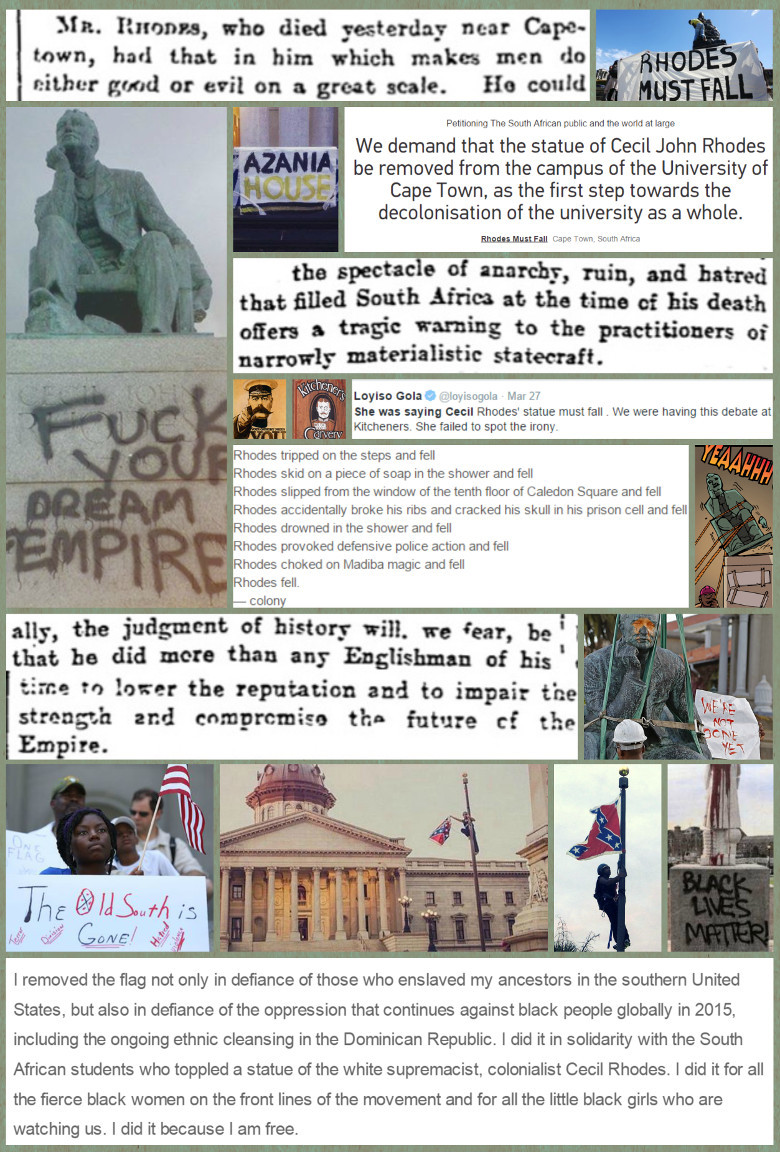

I conclude by coming full circle, back to where this history of southern African mashups began, in Zimbabwe, and a reference to the colonialist that country was named for, in the 2015 social media campaign #RhodesMustFall. The demands for the removal of statues of Cecil John Rhodes launched a protest movement in South African universities that spread internationally. There was so much content to curate in this debate that I was inspired to… mash it up.